Akhand Bharat

Cambodia India ties, India's flagship developmental schemes, India-Nepal rocky high, Nepal between India and China, Akhand Bharat map troubles, India's control of Kashmir

UPDATE: King Norodom Sihamoni of Cambodia recently visited India celebrating 70 years of diplomatic relations. The Kingdom's exports to India have surged by 64% compared to the same period last year.

A key conceptual and operational modality in which Government of India (GOI) conducts developmental activity in economic and social sectors for the welfare of its citizens are its flagship developmental schemes and programmes.

The recent visit indicates that India and Nepal are moving beyond their fraught phase and taking this “hit” relationship to “Himalayan Heights.” They signed five projects and six MoUs for hydropower, connectivity, and people-to-people relations.

Akhand Bharat is a term used by right-wing groups for a map of India that includes parts of Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Afghanistan. The groups dream of a day when the unification of these countries with India will become a reality.

When India revoked the disputed Kasmir’s autonomous status, it sparked fears of diplomatic—even nuclear—war. However, Narendra Modi’s government seems to have succeeded at bringing the region under its direct authority.

India and Cambodia strengthen their relationship

King Norodom Sihamoni recently visited India and received a ceremonial welcome from Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Droupadi Murmu - 15th President of Republic of India. India and Cambodia are celebrating 70 years of diplomatic relations this year. In the wake of the King's visit, it has come to light that the Kingdom's exports to India have surged by 64% compared to the same period last year, and there are reasons to believe that the best is yet to come.

India provides Cambodia with support in terms of technical training and scholarships through the Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR). Additionally, there are military ties that provide the Cambodian Army with equipment and training. During the King's visit, Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar, discussed capacity building, conservation of architectural monuments, and parliamentary collaboration.

Karthik Tallam, Cambodia's Honorary Consul in Bangalore for the South Indian States, and Devyani Khobragade, the Indian Ambassador in Cambodia, were among the organizers of the trade mission. Khobragade stated "An economic partnership between the two nations, particularly in the high-tech/fintech sector, would be a win-win situation." Tallam noted that after the visit, these delegates are returning to India as ambassadors of Cambodia, impressed by the country's business-friendly environment and expressing confidence that this engagement would continue.

Anthony Galliano, Group CEO of Cambodian Investment Management Holdings, strongly believes Cambodia's will become the Asian Tiger of the 21st Century. He highlighted Cambodia's high level of dollarization, which makes the country attractive to investors by minimizing the risk of sharp exchange rate adjustments and mitigating capital flight. Additionally, foreign companies registered as qualified investment projects (QIPs) are eligible for further tax exemptions or special tax depreciation. Also, the growing middle class is an indicator of increasing demand in the real estate and service sectors.

Yashi Dhariwal, head of the Political & Economic Department of the Honorary Consul, is optimistic about the future of Cambodia-India relations. She remarked, "It is the first time that such a significant business delegation from India has visited Cambodia. The feedback we received from them is positive."

There is well-founded optimism in the Kingdom today. Those who recognize it are discussing it, and those who are aware are taking action.

A key conceptual and operational modality in which Government of India (GOI) conducts developmental activity in economic and social sectors for the welfare of its citizens are its flagship developmental schemes and programmes.

In recent years, the Government has made a concerted effort to align its foreign policy objectives with its domestic development priorities. It is partnering with other countries on its flagship schemes and programmes such as Make in India, Skill India, Start-Up India, Namami Gange, Digital India, etc.

GOI flagship schemes are increasingly finding mention among policy makers in the Ministry of External Affairs, particularly in the verticals labelled as: (a) ‘Diplomacy for Development’ i.e. partnering with developed countries to fulfil India’s developmental requirements; and (b) ‘Development Partnership’ i.e. partnering with developing countries of the Global South to share India’s experiences and expertise to fulfil their developmental needs.

The present publication aims to gain a better understanding of how development objectives can be served by aligning Indian diplomacy with flagship schemes of GOI in social and economic sectors and by exploring avenues of cooperation with foreign countries in relation to these schemes. The publication includes papers on Start-Up India, Digital India, UPI, National Education Policy 2020, and Ayushman Bharat.

Dr. Ajai Chowdhry, Founder, HCL Technologies Ltd., makes a case for turning India into a ‘product nation’ especially in the electronics sector through incentivising Start-Ups to localize manufacturing, invite FDI and create new global supply chains. Deepak Maheshwari, Public Policy Consultant and Researcher and Founder, NIXI, emphasizes that India is emerging as an exemplar par excellence when it comes to deployment of digital technology for mass impact and proposes that India should share its expertise & experience in Digital Public Infrastructure including through spearheading an International Digital Alliance on the lines of the International Solar Alliance. Avni Sablok from ICWA writes about the success of UPI – a key element of the Digital India programme – and Indian diplomacy’s efforts to make it go global. Prof. Sudhanshu Bhushan, Vice Chancellor, National University of Educational Planning and Administration (NUEPA) highlights the possibilities provided by the New Education Policy for internationalization of higher education through attracting foreign students

to study in India and through global exposure of Indian students and faculty and makes recommendations for policy implementation. While essaying the implementation till date of the two components of Ayushman Bharat – Health and Wellness Centres (HWCs) and Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PM-JAY), Prof. Mayur Trivedi from the Indian Institute of Public Health, Gandhinagar expresses the view that, as a health system in transition, India is at a juncture wherein it can share its experience in improving health indicators with low-performing countries of the Global South and also learn from better- performing countries.

ICWA hopes that this publication would be useful not only for foreign policy practitioners and scholars with an interest in strengthened linkages between India’s domestic priorities and foreign policy objectives but also for those having an interest in Government’s domestic flagship developmental programmes and schemes and their success.

Download the PDF here.

India and Nepal Rocky Mountain High

By visiting China in 2008, Pushpa Kamal Dahal, also called Prachanda, became the first Prime Minister to break the tradition of Nepalese premiers choosing India as their maiden destination of visit. Fast forward to June 2023, Mr Prachanda not only chose India to be his first destination but also expressed contentment with his four-day visit, dubbing it an “astounding success”. The recent visit indicates that India and Nepal are moving beyond their fraught phase and taking this “hit” relationship to “Himalayan Heights.” During these four days, both countries prioritised convergences over divergences – they signed five projects and six MoUs. Areas such as hydropower electricity, connectivity, and people-to-people relations remained the centre of this fruitful engagement.

Hydropower cooperation was at the top of the agenda. In recent years, India has taken the lead in accelerating this win-win partnership. In November 2021, India began to purchase Nepal’s hydropower electricity and permitted it to export 452 MW. As a result, in 2022 alone, Nepal’s hydropower electricity exports generated a revenue of ~12 billion. Building on this momentum, India and Nepal have now agreed to increase the latter’s hydropower export quota to 10,000 MW over the next 10 years. They also signed new MoUs for Indian firms to develop Arun and Karnali hydropower projects and agreed to act swiftly on the detailed report of the Pancheswar Multipurpose Project. Additionally, India also agreed to facilitate Nepal’s hydropower exports to Bangladesh.

Connectivity, trade, and people-to-people contacts also took precedence during the visit. Both countries signed MoUs for a cross-border petroleum pipeline, cross-border payments, infrastructure development for check posts, and cooperation between foreign service institutes. They also renewed the Transit Treaty, virtually inaugurated integrated check posts, and flagged the inaugural run of a cargo train from India to Nepal.

Both countries signed MoUs for a cross-border petroleum pipeline, cross-border payments, infrastructure development for check posts, and cooperation between foreign service institutes.

Throughout the visit, the two leaders focussed on areas of convergence that are mutually beneficial rather than attempting to resolve contentious and sensitive issues. Although both sides agreed to settle the border dispute, there was no in-depth engagement on the same. This finite focus on mutually beneficial areas is due to India’s neighbourhood policy, Nepal’s domestic developments, and geopolitics.

Following the alleged 2015 Nepal blockade, India has focussed on perception management and has shied away from commenting on Nepal’s domestic developments. Its Neighbourhood First policy has prioritised accommodating its neighbours’ interests, economic needs and aspirations through economic integration and connectivity. This is despite increasing criticism of India’s foreign policy from Opposition parties.

Domestically, Nepal continues to be politically unstable. The lack of a clear majority in parliament and the recent unveiling of the Bhutanese refugee scam have kept Mr Prachanda’s fragile alliance on its toes. The domestic environment limits his ability to seek a non-partisan consensus on solving Nepal’s major issues with India. It is also likely that Mr Prachanda focussed on mutually beneficial areas, as discussing contentious issues would have triggered criticism from different political parties based on their partisan policies.

Nepal’s economy is in bad shape as well. It is facing food and fuel inflation, shortage of essential commodities, and depleting foreign reserves. Kathmandu is experiencing a recession with an increasing trade deficit, Inflation, unemployment and declining foreign direct investments. Currently, Nepal is also seeking assistance from an Extended Credit Facility offered by the International Monetary Fund. Thereby, its immediate focus is on containing inflation, maintaining foreign exchange reserves, raising capital, and reducing the trade deficit, in which trade and economic integration with India is crucial.

Kathmandu is experiencing a recession with an increasing trade deficit, Inflation, unemployment and declining foreign direct investments.

Geopolitically, despite China’s infrastructure and assistance, Beijing has fallen short of Kathmandu’s expectations. Border infrastructure remains underdeveloped, and the trade deficit with China has grown disproportionately. Beijing has continued to turn a blind eye to Nepal’s request for grants to proceed with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects. As such, none of the nine projects have been implemented to date. China has also begun to intervene in Nepal’s internal politics to further its interests. A desperate China is even propagating Pokhara International Airport as part of its BRI, though Nepal has denied the claim. China’s limitations in being a viable alternative to Kathmandu have thus compelled the country to focus on beneficial Indian projects and partnerships.

That said, India-Nepal relations are not free from irritants. Nepal continues to urge India to amend the 1950 treaty. It has requested India to open new air routes, reverse anti-dumping measures, and resolve boundary issues. Adding to Nepal’s anxiety, India has also restricted its markets to Chinese-assisted Nepali infrastructure projects, hydropower plants, and airports. While both countries have no choice but to resolve these issues, engagements on such contentious matters require more trust and an opportune time.

The success of the recent visit, however, illustrates that both India and Nepal are increasingly realising the mutual benefits of their partnership and cooperation. They recognise the strategic importance of each other in the evolving global order and have maintained a positive momentum despite some political challenges and divergences. It is only through such sustained engagement that they will be able to address their mutual suspicions and build trust.

Read original article here.

Nepal balanced between India and China

By Zhang Jiadong

NEPAL'S Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal, ak.a. Prachanda, concluded his four-day visit to India on last Saturday. This visit has continued a tradition of new Nepali leaders making New Delhi their first foreign port of call after assuming office. This is the fourth visit of Prachanda to India as Prime Minister of Nepal and his first overseas trip after taking office in December 2022. This visit is of particular significance as it takes place during a period of strained relations between China and India.

Both Nepali and Indian media have taken an optimistic view of this visit, considering it an important event in Nepal-India relations. The External Affairs Ministry in New Delhi said the visit continues the tradition of "regular high-level exchanges between India and Nepal in furtherance of our 'Neighborhood First' policy." But in fact, Nepal is following its own diplomatic tradition of prioritizing neighboring countries, particularly India. Traditionally, Nepali leaders choose India as their first overseas destination after taking office. From India's perspective, this demonstrates that Nepal is adhering to India's Neighborhood First principle, which means that India's neighboring countries should prioritize India's concerns and national interests.

Specifically, this visit has several key points: Firstly, Prachanda led a substantial delegation of over 100 members comprising senior officials as well as business and industry leaders. It demonstrates Nepal's importance attached to this visit and points to the wide range of topics covered in the discussions during the visit.

Secondly, the visit focused on economic issues. A slew of agreements of long-term importance was signed. One of the great results of the visit is the signing of a long-term power-sharing agreement, under which India has agreed to purchase 10,000 megawatts of electricity from Nepal in the next 10 years. The deal "marks an important milestone in our bilateral ties," said Prachanda.

During the visit, both sides appreciated the progress made in the construction of the 900 MW Arun-3 hydroelectric project in Nepal. They also jointly carried out the groundbreaking of the 400 kV Gorakhpur-Butwal transmission line and welcomed the decision of the Indian government to fund the Bheri Corridor, Nijgadh-Inaruwa and Gandak Nepalgunj Transmission lines and associated substations. These projects, once completed, will further strengthen Nepal's one-way economic dependence on India.

Nonetheless, it's noticeable that Nepal remains highly focused on maintaining a balance between China and India. India continues to be the dominant country in Nepal's affairs, but China's influence in Nepal is also rising. To hedge the potential impact of Prachanda's visit to India, it's reported that Prachanda is likely to visit China next month or in early August. If it was true, this will attest to Nepal's way of balancing between China and India. India is Nepal's "big brother" that can determine Nepal's fate, while China is Nepal's "friend" that can impact Nepal's economic development. Sandwiched between these two major powers, Nepal is unwilling to, and cannot afford to, offend either.

In recent years, India has taken many measures in Nepal to weaken the relationship between China and Nepal. On one hand, India has given the green light to cooperation between the US and Nepal, attempting to leverage US power to diminish China's influence in Nepal. The ratification of the highly controversial Millennium Challenge Corp. Nepal Compact in 2022 would not have been possible without India's consent. On the other hand, India has actively competed with China over major projects in Nepal. India has banned the import of electricity from Nepal that is linked to Chinese investment or involvement, be it equipment, workers, or subcontractors, a move that restricts the development of Nepal's hydropower industry. This reflects India's influence in Nepal and highlights the inevitable geopolitical and economic challenges in China-Nepal trade cooperation.

The core of Nepal's policy toward China and India is to keep Nepal neutral and independent. The Himalayan country tries to strike a balance between China and India, carefully assessing the relative influence of China and India in Nepal and adjusting its policies accordingly. However, it is indeed becoming increasingly challenging for Nepal to maintain a balance between neutrality and seeking its own development, as seeking development necessitates improving relations with both China and India.

Prior to Prachanda's visit to India, Nepal's Foreign Minister Narayan Prakash Saud said in an interview that the government would continue to maintain good relationships with both countries and would not do anything to hamper ties with either of the neighbors. After all, being neutral is in the best interests of Nepal, and the country knows this well.

Read original article here.

Akhand Bharat map in India’s new parliament upsets neighbours

Bangladesh, Nepal and Pakistan express displeasure over ‘Undivided India’ mural in the recently inaugurated building. Akhand Bharat is a term used by right-wing groups for a map of India that also includes the geographical parts of Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Afghanistan. The right wing groups claim that the Indian sub-continent and these countries were bound by a common "culture" and dream of a day when the unification of these countries with India will become a reality.

The installation of a map in India’s newly inaugurated parliament building has riled its South Asian neighbours, including Bangladesh, Nepal and Pakistan. Bangladesh’s foreign ministry on Monday sought an explanation from New Delhi over the Akhand Bharat, or Undivided India, map in the new parliament building, inaugurated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi late last month.

The map includes parts of Afghanistan, and the entire Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Myanmar. The Bangladeshi embassy in the Indian capital has been instructed to contact India’s foreign ministry to get India’s official explanation on the matter, Bangladesh’s junior minister for foreign affairs, Shahriar Alam, told reporters in Dhaka.

“Anger is being expressed from various quarters over the map. There is no reason to doubt … the installation of the map. However, we have asked our mission in New Delhi to speak to the Indian ministry of external affairs to find out what their official interpretation is,” Alam said.

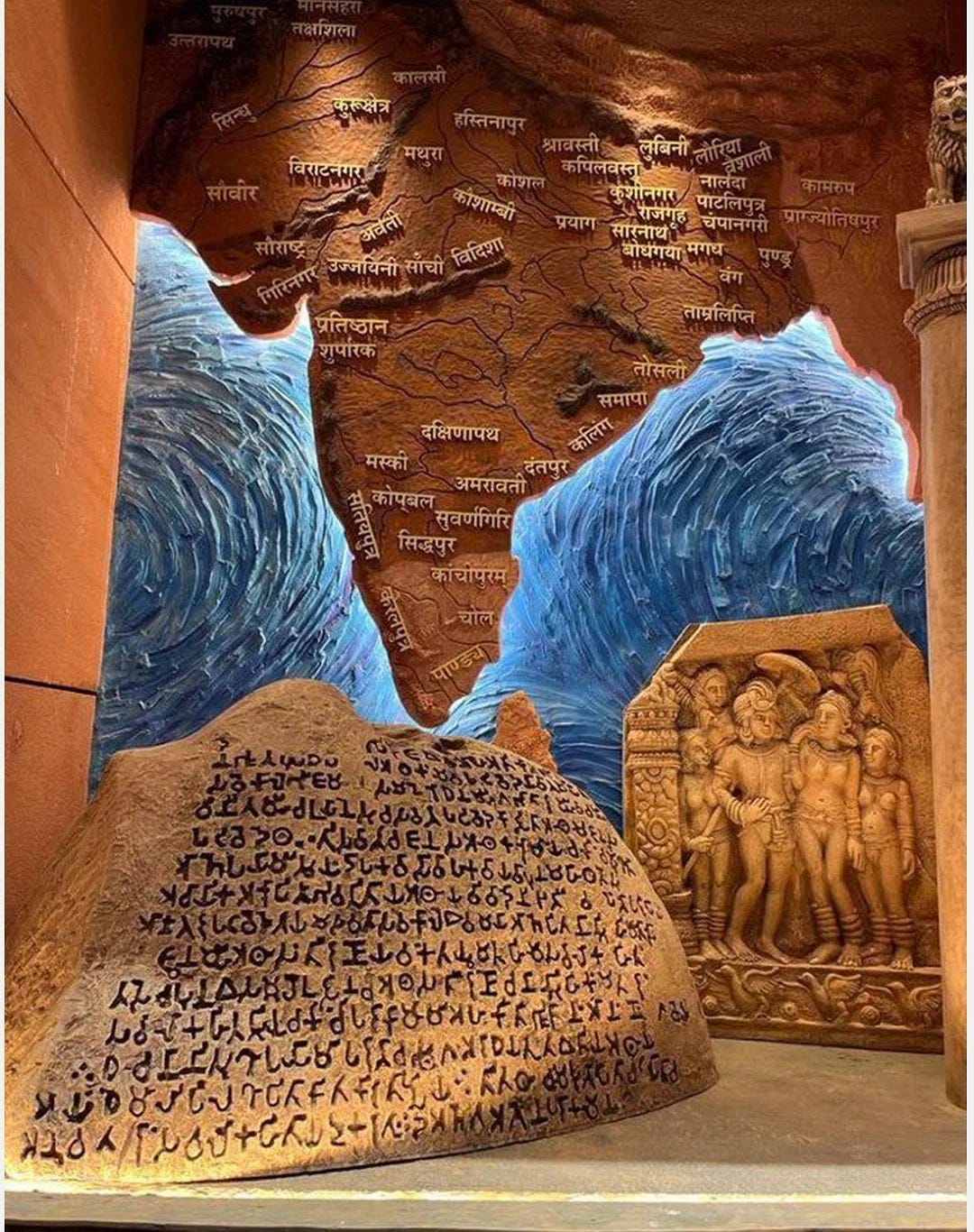

India’s foreign ministry spokesperson Arindam Bagchi said in a media briefing the mural depicts the spread of the ancient Mauryan Empire and “the idea of responsible and people-oriented governance that [King Ashoka] adopted and propagated”.

However, during the inauguration of the new parliament building on May 28, India’s minister for parliamentary affairs as well as coal and mines, Pralhad Joshi, had described the mural as a map of the Akhand Bharat – a decades-old, right-wing fantasy that imagines an ethnic Hindu nation in the subcontinent.

“The resolve is clear – Akhand Bharat,” says a translation of Joshi’s tweet.

Joshi’s reference to some idea of an “undivided” India did not go down well with its neighbours.

“If a country like India that sees itself as an ancient and strong country and as a model of democracy puts Nepali territories in its map and hangs the map in parliament, it cannot be called fair,” Nepal’s former Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli was quoted as saying in The Kathmandu Post newspaper.

Oli asked the Nepalese Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal, who visited India last week, to “ask [the Indian government] to remove the mural” and “correct that mistake.”

“There is no point in visiting India if you can’t do that,” Oli told the Nepalese newspaper.

According to Indian media reports, Dahal did not raise the map in his meetings with his Indian counterpart, Narendra Modi, or other officials.

The mural depicts Nepal’s ancient sites such as Lumbini – the birthplace of Lord Buddha – and Kapilvastu as part of the “Greater India” map.

Last week, Pakistan also expressed ” grave” concerns over the idea of Akhand Bharat being increasingly peddled by India’s ruling dispensation.

At a weekly news briefing in Islamabad, Pakistani foreign ministry spokesperson Mumtaz Zahra Baloch said the assertion in the map was “a manifestation of an expansionist mindset that seeks to subjugate the ideology and culture not only of India’s neighbours but also its religious minorities”.

So far, there has not been any official statement from Sri Lanka, Afghanistan or Myanmar on the matter.

Read more here.

Modi Took Complete Control of Kashmir Two Years Ago—and Got Away With It

By Anchal Vohra (edited)

When India revoked the disputed valley’s autonomous status, it sparked fears of diplomatic—even nuclear—war. Two years after the Indian parliament revoked the autonomous status of Indian-administered Kashmir, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government seems to have succeeded at bringing the region under its direct authority.

Condemnation from the international community has been cautiously worded and limited. When U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken last visited India, Kashmir was not a major issue even if spoken about behind closed doors. For the first time, in a long time there is peace on the de facto border between India and Pakistan, cross-border infiltration has paused, and militancy has dipped. According to the latest data from the Indian government, the number of terrorist incidents in Jammu and Kashmir fell by 59 percent last year, compared to the year before, and by 32 percent up to June this year compared to the same period last year.

The above successes have not been good news for average Kashmiris, who feel politically disenfranchised and silenced into acquiescence. Most Kashmiris welcomed dividends of peace but not being forced to capitulate to New Delhi’s wishes.

On Aug. 5, 2019, Modi’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) not only abrogated Article 370, under which the local legislature could make its own laws except in finance, defense, foreign affairs, and communications, but it also revoked Article 35A, which empowered the legislative assembly to define permanent residents and offer them special privileges such as exclusive land rights. Modi also split the three different divisions of the erstwhile state—Jammu, Kashmir, and Ladakh—into two union territories. While a state has its own government and powers to pass laws, union territories are much smaller administrative units ruled by an appointee of the central government.

The Indian government deployed a slew of suppressive measures to deter Kashmiris from expressing their will publicly. It deployed masses of troops, intimidated tens of journalists, and carried out large-scale arrests of Kashmiri politicians, secessionists, and anyone with enough clout to mobilize popular discontent into a sustained agitation. While mainstream politicians were subsequently released, thousands of Kashmiris are still believed to be languishing in prisons inside Kashmir and across the country.

India quietened the international community by refusing to allow protests that could have turned violent and made it harder for India to retain Western support. India also threw around its economic weight as a counterbalance to China, dangled investment opportunities in front of some countries, and threatened withdrawal of lucrative business contracts from the last two remonstrators, Turkey and Malaysia, which openly criticized India on Kashmir. “In the end, the U.S.’s support was most necessary, and they backed India because of larger geopolitical concerns re: China,” the former Indian diplomat added.

India has undoubtedly defeated Pakistan in this bout of their prolonged and intractable conflict. Islamabad fumbled while New Delhi rallied quiet support from the Western world and even brought the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia to temper Pakistan’s expectations. The UAE has acknowledged it played a role in getting the two rivals to agree to a cease-fire. Over the last two years it has also become clear that Indian diplomats have crushed Pakistan’s hopes of a U.N.-led plebiscite to settle the Kashmir dispute. But that does not mean India has eliminated all challenges.

Meanwhile, India is building the world’s largest rail bridge to connect Kashmir in the Himalayas to Kanyakumari on its southernmost tip. But Modi and his government are a long way off from reducing the distance between New Delhi and the Kashmiris. India’s promise of economic development is insufficient to win them over unless it comes with the freedoms offered in a democracy. The Modi government displayed masterly statecraft in its clampdown on the valley, but it also revealed its authoritarian streak.

Read more here.