Show me the money!

While China's growth story continues, as does the rise of decentralised finance in the form of Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs), global wealth shifts East and neo-liberalism gets an obituary

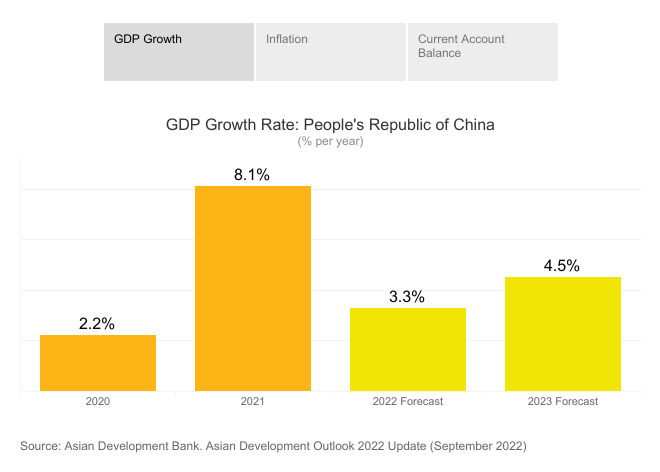

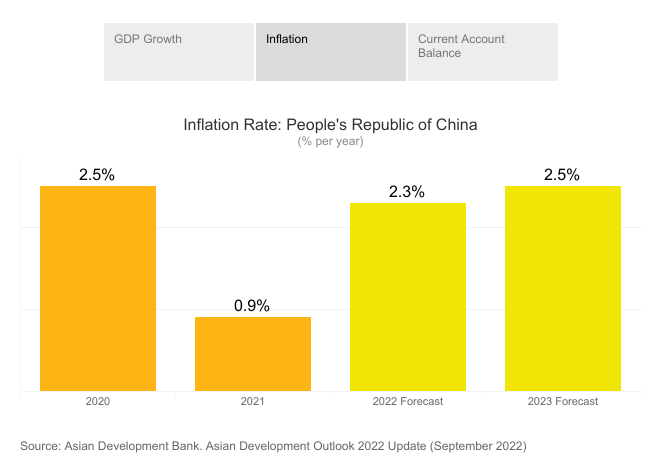

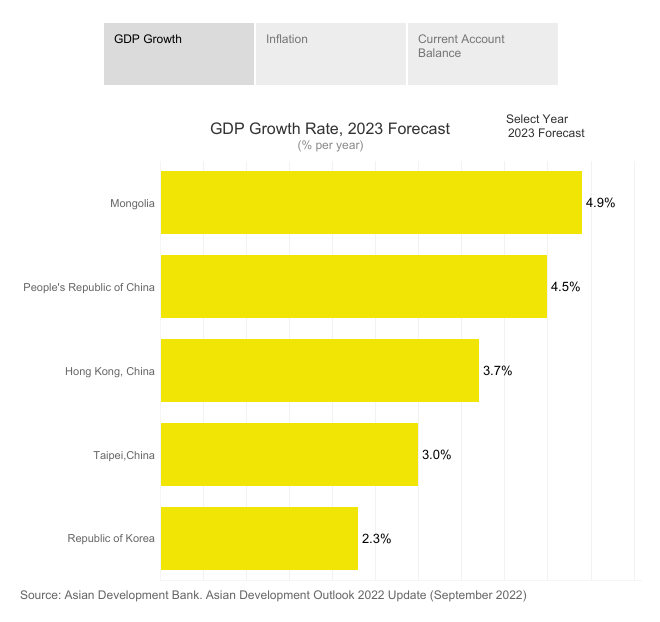

UPDATE: The Long Mekong Weekend takes an in-depth look at China’s economy. Despite the furore in Anglo-American press about Covid-19, every major international bank and financial services providers are upbeat on China predicting growth over 4.5%. The same cannot be said for the tail-end of neo-liberalism and its discredited policies, which have undermined education, health, infrastructure and social cohesion while massively increasing debt and fuelling endless wars. The new global wealth patterns are moving further and further east and from north to south. The collapse of FTX and Bitcoins decline indicates that CBDC, which ensure end to end encrypted digital payments are decentralising the US-led reserve currency system. Enjoy your Long Mekong Weekend!

Report on China for Q4 2022

Overall, we expect China’s overall economic policy to remain supportive next year as recovery is still fragile. As such, we expect China’s GDP growth rate to pick up in 2023 from this year’s low level.

China’s GDP grew 3.0% year-over-year (yoy) in the first nine months of 2022. Q3 GDP grew 3.9%, 3.5 percentage points higher than Q2, better than market expectations. On a quarter-over-quarter basis, the economy grew by 3.9% in Q3, a significant improvement from -2.6% in Q2. The Covid-19 pandemic, slowdown in the real estate market, and ongoing geopolitical challenges continued to affect China's economic growth in Q2. Growth momentum improved in Q3, showing the resilience of the Chinese economy.

The 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) was held in 16-22 October. The Congress outlined focus areas for the country's continued path towards high quality development , with the aim to achieve the goal of becoming a ‘socialist modern power’ by the mid-century. To achieve the goal, we estimate that China’s economy still needs to grow on average 4.5% per annum through 2035. In addition, innovation and national security were emphasised as two key themes for China’s future growth. We expect China’s R&D spending will continue to rise, led by government-guided investment funds.

With more policy support and better weather conditions, industrial production saw a rebound in Q3. Industrial production growth improved from 3.8% in July to 6.3% in September. However, the Purchasing Managers' Index (PMI), a leading manufacturing indicator, had been hovering around the 50 threshold and declined to 49.2 in October from 50.1 in September, suggesting a weakening momentum.

Retail sales growth returned to positive in Q3 after being hard-hit by worsening pandemic conditions in Q2. It rose 3.5% in Q3, beating market expectations. Driven by supply chain improvements, reduced purchase tax, and lower base for comparison, auto sales have shown a strong rebound since June, up 18.2% in Q3. However, service consumption remained anaemic, due to both the ongoing pandemic situation and low consumer confidence.

The property market faces continued pressure. Real estate investment fell by 12.7% in Q3 from a year ago, 3.6 percentage points lower than that in Q2. Funding constraints have been a key challenge faced by developers, especially those with high leverage ratios. The government has taken actions to stabilise the market. In November, the PBoC and CBIRC jointly issued a package of 16 measures to bolster financing of the property sector. We expect the property market to remain weak in the near term but will gradually stabilize next year.

China’s National Health Commission (NHC) released a circular in early November 2022, announcing 20 new measures to further optimise the COVID-19 control measures. While the government maintains its ‘Zero Covid Policy’, these measures signal a gradual shift and reopening. We expect more fine-tuning in the next several months to effectively contain the virus while minimising its impact on economic and social development.

Download the full Q4 report here.

CPC Central Economic Work Conference 2022

Overview of CPC Central Economic Work Conference

The annual Central Economic Work Conference was held in Beijing from Wednesday to Friday as Chinese leaders mapped out priorities for the economic work in 2022.

In a speech at the conference, Xi Jinping, general secretary of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee, Chinese president and chairman of the Central Military Commission, reviewed the country's economic work in 2021, analyzed the current economic situation and arranged next year's economic work.

The year 2021 has been a milestone for both the Party and the nation, according to the meeting, which noted that China has maintained a leading position in the world in economic development and epidemic control, with progress made in scientific strength, industrial chain resilience, reform and opening-up, people's livelihood and ecological civilisation.

However, it cautioned that China's economic development is facing pressure from demand contraction, supply shocks and weakening expectations, and the external environment is becoming increasingly complicated, grim and uncertain.

"We must face the difficulties squarely while staying confident," said a statement released after the meeting, citing China's strong economic resilience and unchanged fundamentals underpinning long-term growth.

The meeting called for remaining committed to China's own cause, consolidating the economic foundations, enhancing the abilities of scientific and technological innovation and adhering to multilateralism.

Read full article here.

Growth in the global balance sheet accelerated during the pandemic, but paused in 2022.

The global balance sheet takes stock of the wealth and health of the global economy, looking at the assets and liabilities of households, corporations, governments, and financial institutions. For nearly three decades, the global balance sheet continuously grew faster than GDP, as described in MGI’s 2021 report The rise and rise of the global balance sheet: How productively are we using our wealth? This growth then accelerated sharply in the intense first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, in 2022, early signs of a possible inflection point appeared, with greater volatility in the components of the global balance sheet and the first overall shrinkage in decades.

The global balance sheet expanded inexorably from 2000 to the end of 2021. Real assets and net worth; financial assets and liabilities held by households, governments, and nonfinancial corporations; and financial assets and liabilities held by financial corporations each grew from about four to more than five times GDP. Global net worth was $610 trillion at the end of 2021. Only about one-fifth of wealth growth came from savers channeling money into new investment, with asset price inflation on the back of low interest rates contributing close to 80 percent. Correspondingly, liabilities and debt in China, Europe, Japan, and the United States were higher relative to GDP at the end of 2021 than at the time of the 2008 global financial crisis. For every dollar of net investment, $1.90 of additional debt was created outside the financial sector.

Download full report here.

Cryptocurrencies and Decentralized Finance (DeFi)

The financial system performs a wide array of functions that are important for eco- nomic growth and stability, such as allocating resources to their most productive use, moving capital from agents with surpluses to those with deficits, and providing efficient means for moving wealth across time and states, see for example Merton (1995) or Allen et al. (2019).

To achieve these goals, the US financial system, and similarly most other countries, have traditionally relied on a set of intermediaries such as banks, brokers, exchanges etc. that are connected by payment systems. These intermediaries serve as centralized nodes that guard the access to the financial system and provide customers with essential services such as record keeping, verification of transactions, settlement, liquidity, and security. This architecture implies that intermediaries perform many of the core functions in the system, and also help with the implementation of regulatory goals such as tax reporting, anti-money-laundering laws or consumer financial protec- tion. As a result, however, these intermediaries can hold significant power, based on their preferential access to customers and data. This centralized position, if not prop- erly harnessed and regulated, can be a source of outsized economic rents and can lead to considerable inefficiencies. It can also lead to inherent fragility and systematic risk if core intermediaries become corrupted or investors lose trust in the system.

Download the full paper here.

The slow demise of neoliberalism

How the all-conquering movement contained the seeds of its own destruction. Like most political terms, “neoliberalism” is used so loosely that many people have suggested it’s no more than a general pejorative. But the ideas and institutions that emerged from the economic chaos of the early 1970s undoubtedly differed in fundamental ways from those of the decades after 1945 and clearly deserve their own name. That these ideas and institutions have lost much of their power is just as obvious, even if nothing coherent has emerged to replace them.

That, at any rate, is the conclusion reached both by Brad DeLong in his new book, Slouching Towards Utopia: An Economic History of the Twentieth Century, and by Sebastian Edwards in his forthcoming book, The Chile Project: The Story of the Chicago Boys and the Downfall of Neoliberalism. Importantly, neither DeLong nor Edwards can be numbered among the neoliberals’ irreconcilable opponents. Both embraced neoliberalism for many years, though in different forms.

The Chile Project, of which Edwards was a generally sympathetic observer, ranks with Thatcher’s Britain as the paradigmatic case of what I’ve called “hard neoliberalism,” which combines authoritarianism and radical free-market policies. The success of the “Chicago Boys” — the economists who have long dominated the Chicago School of Economics — in persuading the Pinochet dictatorship to implement market-driven policies that were largely sustained under subsequent democratic governments. They included a privatised pension system, writes Edwards, along with “openness and globalisation, the fiscal rule, the taming of inflation, and austere health, education, and environmental policies.”

As the examples of Pinochet and Thatcher suggest, hard neoliberalism has nothing in common with the concern for freedom of speech that motivated John Stuart Mill and other liberal thinkers. But it was consistent with the strain of classical liberalism represented by the Austrian-born economist Friedrich Hayek, for example, who was more worried about preserving individuals’ freedom of action, particularly by minimising government interference in property rights.

The “neo” in hard neoliberalism reflects how the successes of social democracy in the twentieth century permanently discredited the kind of classical liberalism that would tolerate mass poverty alongside massive wealth. Neoliberals accepted the need for social services to raise most people above the poverty line. Provided that goal was achieved, they argued, there was no need to be concerned about political and economic inequality.

Read the full review here.