After the Indo-Pacific Storm

An Indo-Pacific Storm is rising and ASEAN is resisting US centrality. Meanwhile, the ASEAN + 1 arrangement remains the global economic engine.

UPDATE: The Long Mekong Daily takes a deep-dive into current research perspectives on the New Cold War. The Indo-Pacific storm is threatening to overwhelm the region and create US centrality in ASEAN. However, poor economic choices and recession are eroding the US, EU and Japanese economies while ASEAN +1 remains the engine of global growth. Will the Indo-Pacific storm recede to reveal US overstretch? And, can ASEAN move to a future of further integration free from extra-regional interference?

In ‘The Leviathan’, Hobbes (2018) discusses the notion that freedom is the power to act without interference – where the absence of interference, by external actors, is what confirms the presence of freedom.

Business and Politics special issue on the Politics of the U.S.-China Trade War has been released earlier this month. A short blurb for the special issue can be found here. The full issue is on Cambridge Core now, with free access until 15th January. (see below)

ASEAN and Great Power Rivalry

The political situation in Southeast Asia is basically stable. ASEAN has announced that it has largely overcome the threat of the epidemic and resumed normal economic activities. Prime Minister Hun Sen of Cambodia, the rotating chair of ASEAN, said that the overall growth rate of ASEAN will reach 5.3% in 2022, which is a remarkable achievement compared to other regions of the world. The main task for ASEAN in the coming period is to focus on economic recovery and to deal with security risks in food, energy and finance.

Four major external factors are impacting ASEAN's diplomacy and security. The strategic game between China and the US is global and decisive, leading to an accelerated reorganisation of the Asia-Pacific region and reducing the space for ASEAN countries to "choose sides". The crisis in Ukraine has further exposed Southeast Asian countries, which have been "ravaged" by the epidemic, to an energy and food crisis. The crisis in Ukraine and the warming situation in the Taiwan Strait are superimposed on each other, and under the international malicious public opinion hype and influence of "today's Ukraine, tomorrow's South China Sea" and "today's Ukraine, tomorrow's Southeast Asia", the "sense of worry" of some Southeast Asian countries has "The security stance and policy adjustments of each country are further differentiated.

Read the full article here.

ASEAN's Handling of Great Power Politics

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), which serves as the linchpin of regionalism in East Asia, is facing a new challenge of great power politics. This article explores ASEAN's position in and strategy for taking cooperative regional initiatives by referring to the management of confrontational politics between rival states.

It explains ASEAN's handling of great power politics theoretically by impartial enmeshment for managing great powers’ material interests and moral legitimacy in developing specific ideational frameworks. This article argues that ASEAN managed great powers’ rivalry by enmeshing them into its regional initiatives impartially and maintaining organisational legitimacy by developing systems of socio-cultural norms. It also contends that ASEAN needs, in envisioning the future of Indo-Pacific regionalism, to extend its strategic reach through alignments with other parties and enhance moral legitimacy by deepening and broadening normative frameworks for advancing collective interests for the Indo-Pacific region.

Download the full article here.

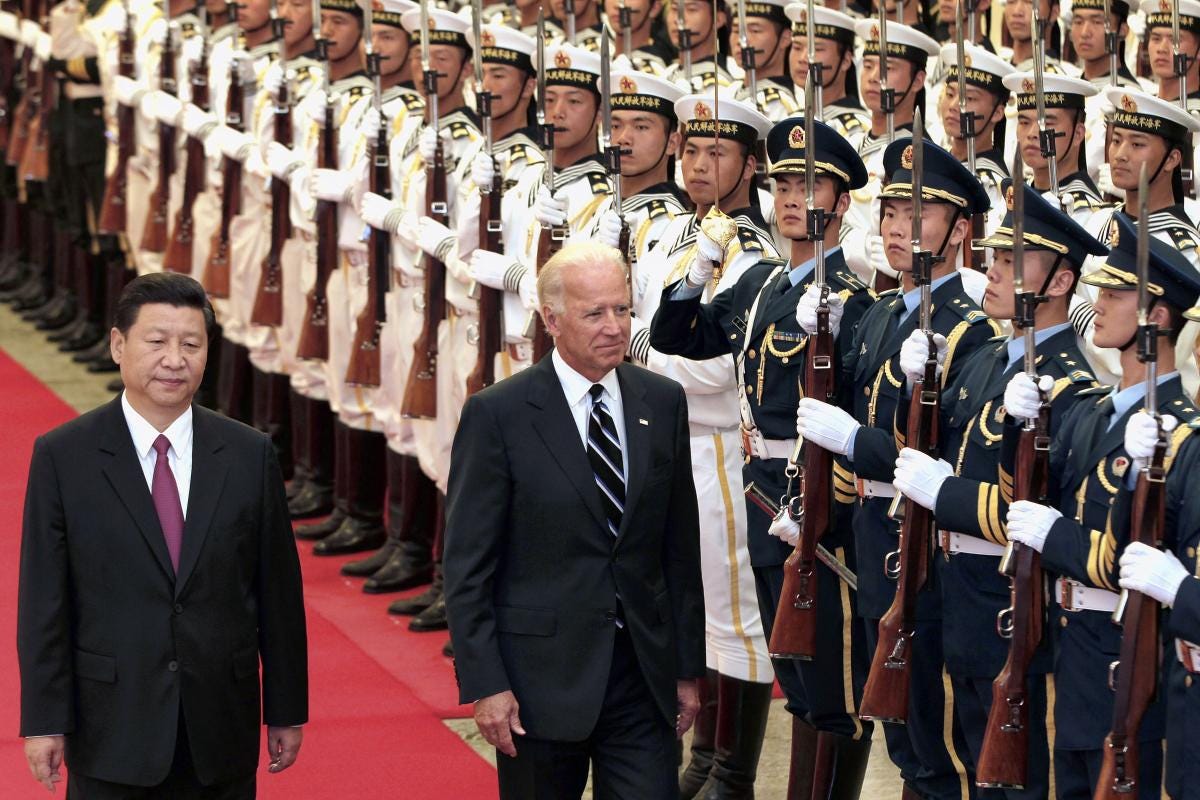

‘ASEAN Centrality’ in an Era of Renewed Power Politics

Regional engagement has increasingly transcended ASEAN through bilateral, trilateral, and plurilateral initiatives that are outside of the ASEAN framework. November was summit season for Asia, with the G-20 Summit held in Jakarta on November 15-16 and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit held in Bangkok on November 18-19. These events took on added importance amid a string of global crises demanding a multilateral response, from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to food and energy price pressures and signs of an impending global recession. The G-20 Summit in particular was in the spotlight as the setting for the first in-person meeting between U.S. President Joe Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping, as well as some of Xi’s first interactions with other world leaders, both friendly (Australia) and unfriendly (Canada).

Amid these high-profile summits, the meeting of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and ASEAN-led East Asia Summit in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, on November 10-13 may have been overlooked. An organization like ASEAN may seem outdated as “middle power” diplomacy takes a backseat in an era of renewed great power politics. Meanwhile, the regional architecture is undergoing transition as established, open, and inclusive regional initiatives (notably those embedded within the ASEAN framework) are being challenged by newer, exclusive, and functionally-driven initiatives. These range from the Quadto the Supply Chain Resilience Initiative and the AUKUS security pact.

Read the full article here.

This Open Access book explains ASEAN’s strategic role in managing great power politics in East Asia. Constructing a theory of institutional strategy, this book argues that the regional security institutions in Southeast Asia, ASEAN and ASEAN-led institutions have devised their own institutional strategies vis-à-vis the South China Sea and navigated the great-power politics since the 1990s.

ASEAN proliferated new security institutions in the 1990s and 2000s that assumed a different functionality, a different geopolitical scope, and thus a different institutional strategy. In so doing, ASEAN formed a “strategic institutional web” that nurtured a quasi-division of labor among the institutions to maintain relative stability in the South China Sea. Unlike the conventional analysis on ASEAN, this study disaggregates “ASEAN” as a collective regional actor into specific individual institutions—ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ Meeting, ASEAN Summit, ASEAN-China dialogues, ASEAN Regional Forum, East Asia Summit, and ASEAN Defense Ministers Meeting and ASEAN Defense Ministers Meeting-Plus—and explains how each of these institutions has devised and/or shifted its institutional strategy to curb great powers’ ambition in dominating the South China Sea while navigating great power competition.

The book sheds light on the strategic potential and limitations of ASEAN and ASEAN-led security institutions, offers implications for the future role of ASEAN in the Indo-Pacific region, and provides an alternative understanding of the strategic utilities of regional security institutions.

Download the book PDF here.

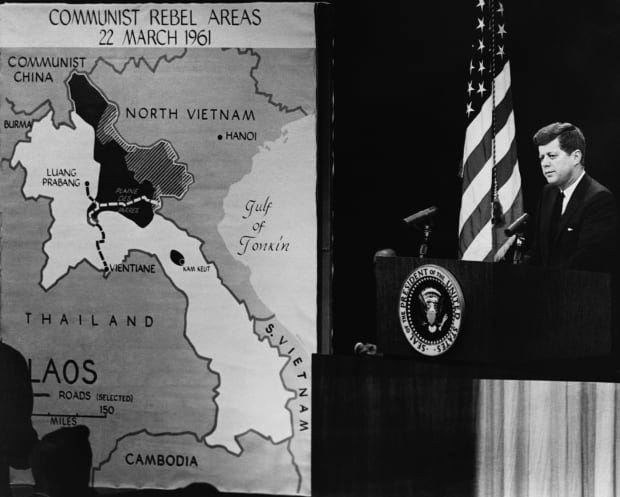

Southeast Asia Before and After the Cold War

The Southeast Asian subsystem is becoming an increasingly important unit of the contemporary international system. Throughout history, the region has got extensive importance for its significant geopolitical location and the abundance of natural resources. That is why a number of external powers, like the United States of America, China, Japan, Russia and India, have engaged heavily to Southeast Asian affairs.

Centuries of Chinese and Indian influence, colonial rule, and more recent imperial interventions have left ineffaceable ideational legacies all over the region.1 Even in the modern era of independent nation-states, outside powers remain vital to the developments of the area. Therefore, the entire region has now become a theatre where great power rivalries and competitions for influence are being played out.

Download the full article here.

Geopolitics, Great Power Competition, and Cambodian Foreign Policy

The post-Cold War global order, grounded in American unipolarity, developed a shared set of institutions and norms that are now in the midst of renegotiation in light of rapid changes in relative power, economic status, power projection capabilities, and domestic political realignments in many of the Western liberal democracies.

As the world prepares to confront a change of administration in Washington with Vice President Joe Biden taking office early next year, expectations among scholars and analysts across the globe are extremely diverse concerning the future equilibrium of the global political structure. In East and Southeast Asia, three potential structures need to be considered when analyzing how Cambodia’s foreign policy can develop over the next twenty years and how Cambodia can best act within the confines thereof: (i) US unipolarity and a ‘status quo ante’ return to American hegemony; (ii) Chinese hegemony; and (iii) Sino-American Bipolarity. Each of these presents distinct challenges and opportunities and will ultimately define the choice sets that all states in Southeast Asia, including Cambodia, will have open to them.

Download the article here.

It has become increasingly commonplace to talk about the possible development of a new Cold War between China and the United States (Rachman 2020). In theory, such a development could offer the prospect of less powerful states playing off one superpower against another in the way the earlier standoff between the United States and the Soviet Union did. Equally possible, of course, is that some regions will find themselves at the center of an intensifying geopolitical struggle that will provide a searching test of their diplomatic skills and capacity to influence strategic contestation between the great powers. Nowhere is more likely to be directly affected and tested than Southeast Asia, a part of the world that once again finds itself at the epicentre of a rapidly changing geopolitical landscape.

In the wake of the United States’ abrupt and chaotic exit from Afghanistan, many of United States’ friends and allies are questioning the value of their formal or informal strategic ties to a hegemonic power that appears to be in relative, if not absolute decline (Sly 2021). Some observers argue that “unless the United States acts to countervail it, China is likely to become the undisputed master of East Asia, from Japan to Indonesia, by the late 2020s” (Westad 2019, 90). In this context, deciding whether the “rise of China” represents more of a threat or an opportunity has rapidly become the quintessential foreign policy question facing the much less powerful, perennially insecure, states that make up the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

Download the full article here.

You might be interested in knowing that the Business and Politics special issue on the Politics of the U.S.-China Trade War has been released earlier this month. A short blurb for the special issue can be found here. The full issue is on Cambridge Core now, with free access until 15th January.