China Lines

Xi Jinping meets Chris Hipkins, New Zealand PM is walking a fine China line, EU line on China receives sharp criticism, US financial conditions harmful to emerging economies

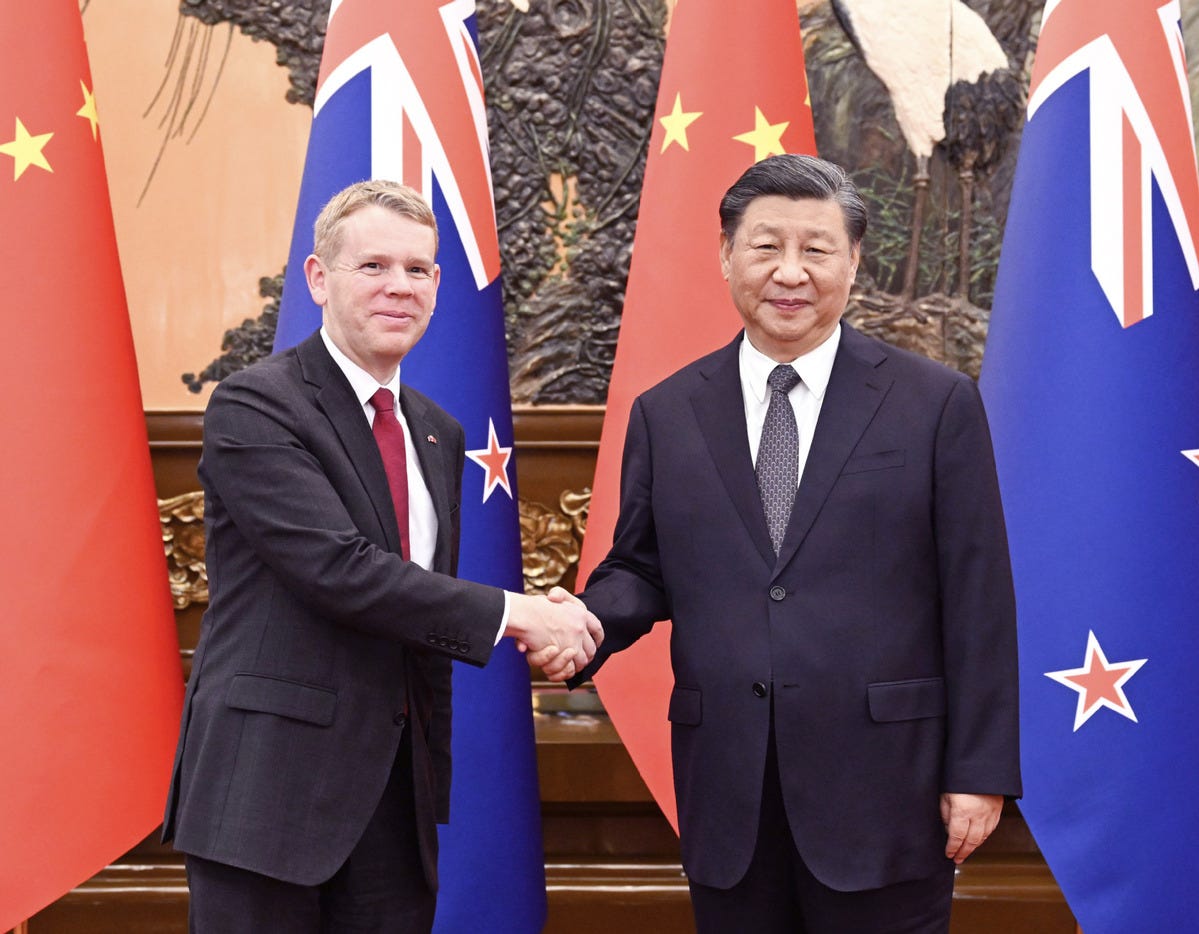

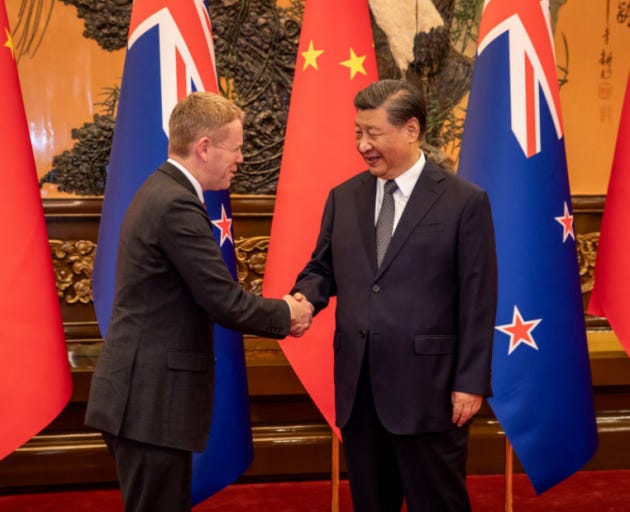

UPDATE: China's emphasis on self-reliance is by no means to adopt a closed-door policy, but to better connect domestic and international markets, Chinese President Xi Jinping said on Tuesday. Xi's remarks came during his talks with Prime Minister of New Zealand Chris Hipkins, who is paying an official visit to China.

Chris Hipkins anticipated a “diplomatic” meeting with Xi Jinping. The Chinese leader said he placed “great importance” on the relationship with New Zealand. Both businesslike, Hipkins made sure to stress his country was open for business too.

When Japan and the Netherlands struck a deal with the US to align with restrictions the Biden administration imposed in October on semiconductor technology transfers to China, the trilateral agreement drew sharp criticism in certain European circles.

Whenever financial conditions in the United States are tightened, some emerging economies with relatively fragile economic fundamentals and high dependence on external financing will face massive capital outflows, currency depreciation, external debt repayment pressures, and even a financial crisis.

Xi meets New Zealand PM Hipkins

China's emphasis on self-reliance is by no means to adopt a closed-door policy, but to better connect domestic and international markets, Chinese President Xi Jinping said on Tuesday. Xi's remarks came during his talks with Prime Minister of New Zealand Chris Hipkins, who is paying an official visit to China.

Xi stressed that, at present, China's central task is to advance the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation on all fronts through a Chinese path to modernization. He said achieving high-quality development is a top priority, common prosperity for all the Chinese people is essential, and making a greater contribution to world peace and development is an important goal for China.

China is such a big country with such a large population that it can only base the development of the country and the nation on its own strength, Xi said.

"Only by opening up can China realize modernization. Development is the top priority of the Communist Party of China in governing and rejuvenating the country. We will continue to vigorously promote high-level opening up and better protect the rights and interests of foreign investors per the law," Xi said.

On bilateral relations, Xi said he attaches great importance to China-New Zealand ties. He recalled his visit to New Zealand in 2014, during which the two countries established a comprehensive strategic partnership.

Xi said the sound and steady growth of China-New Zealand relations over the past decade brought tangible benefits to the two peoples and contributed to regional peace, stability, development, and prosperity.

China has always regarded New Zealand as a friend and partner and is ready to work with New Zealand to embrace another 50 years in bilateral relations and promote the steady growth of China-New Zealand comprehensive strategic partnership, Xi said.

China-New Zealand relations have long been a pacemaker in China's relations with developed countries, Xi said.

Both countries should continue to see each other as partners rather than adversaries and opportunities rather than threats to consolidate the foundation for the growth of China-New Zealand relations, Xi said.

The Chinese president called for a thorough implementation of the upgraded bilateral free trade agreement and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) to advance trade and investment liberalization and facilitation and provide a better business environment for companies to invest and operate in each other's countries.

He noted both China and New Zealand need to step up exchanges and cooperation in education, culture, tourism, and at the sub-national and non-governmental levels so that there can be more people like Rewi Alley, a pioneer in China-New Zealand relations, to boost the bilateral friendship.

Xi called on both sides to jointly advocate true multilateralism and a free trade system and address global challenges such as climate change, adding that they can also help the development of Pacific island countries together.

Hipkins said that last year New Zealand and China celebrated the 50th anniversary of their diplomatic relations, which is a vital milestone in bilateral relations. He said New Zealand attaches great importance to developing relations with China.

Hipkins said he is leading a large business delegation to China to explore more cooperation opportunities and lift bilateral relations to a new level.

New Zealand is willing to strengthen personnel exchanges with China, expand bilateral cooperation in economy, trade, education, science and technology, culture, and other fields, and jointly implement the upgraded version of the bilateral free trade agreement, Hipkins said.

The New Zealand side believes that differences should not define the bilateral ties, and what is important is candid exchanges, mutual respect, and harmony without uniformity, Hipkins said, adding that New Zealand is willing to maintain communication with China on helping develop island countries.

Read more here.

New Zealand’s China Line

By Alexander Gillespie

Chris Hipkins anticipated a “diplomatic” meeting with Xi Jinping. The Chinese leader said he placed “great importance” on the relationship with New Zealand. Both businesslike, Hipkins made sure to stress his country was open for business too.

And there is certainly a good story to tell when it comes to China. Hipkins is building on decades of cooperation, understanding and ground-breaking economic agreements. Bilateral trade was worth NZ$40 billion in 2022 and could reach $50 billion by 2030.

There might even be scope for cooperation over China’s position on a political settlement of the war in Ukraine. Despite New Zealand and most Western nations being sceptical about the initiative, it’s fair to say Chinese authorities would value New Zealand’s input.

But it’s also fair to say Hipkins was wise to visit now, given what he has coming up in his calendar: the NATO summit in July, and a decision on whether New Zealand should join “pillar two” of the AUKUS security pact between the US, UK and Australia.

Both things will concern China. And despite Beijing’s appreciation of New Zealand’s diplomatic approach – including Hipkins’ reluctance to characterise Xi Jinping as a “dictator” – the timing of this red-carpet visit has been ideal.

So New Zealand walks a fine line with China, and beneath the diplomatic niceties there is a growing fault line. When Foreign Minister Nanaia Mahuta visited China earlier this year and expressed New Zealand’s “deep concerns” over human rights, Hong Kong and Taiwan, some media suggested she’d been “harangued” by her Chinese counterpart.

Mahuta has said the conversation was merely “robust”, but there’s no denying China’s combativeness over criticism or threat.

When British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak said China posed “the greatest challenge of our age to global security and prosperity” at May’s G7 summit in Japan (which came on top of an official communiqué tacitly focused on China), Beijing hit back at what it called “smears” and “slander”.

While not part of the G7, New Zealand later added its name to a “Joint Declaration Against Trade-Related Economic Coercion and Non-Market Policies and Practices” that built on the G7 meeting. Although it didn’t explicitly mention China, the declaration clearly articulated concerns over Beijing’s perceived willingness to use trade sanctions against countries that displease it.

This includes South Korea after it installed a US missile defence system, and Australia after it called for an independent investigation of the origins of COVID-19. More recently, China blocked Lithuanian exports after the tiny nation allowed Taiwan to establish a de-facto embassy there.

When New Zealand joined the US in speaking out over the security agreement between China and the Solomon Islands, Chinese state media accused Wellington of smearing and demonising their country and yielding to the influence of Washington.

A few months later, New Zealand reiterated its position to uphold the rule of international law around China’s island-building in the South China Sea. While officially this amounted to not taking sides over competing claims to sovereignty, it effectively rejected China’s historic claims to the area.

And quite recently it was revealed a New Zealand frigate was confronted – professionally but visibly – by Chinese naval vessels while in international waters near the disputed Spratly Islands.

Closer to home, there have been intermittent skirmishes over cyber-security. In 2018, New Zealand’s Government Communications Security Bureau (GCSB) stated it had “established links” between the Chinese Ministry of State Security and a global campaign of commercial intellectual property theft.

New Zealand’s Security Intelligence Service (SIS) has also recently noted agents from a “small number of foreign states” were becoming “increasingly aggressive”, but chose not to identify the culprits.

But when it was reported an analyst within the Public Service Commission had been suspended after being named an “insider threat risk” by the SIS, the Chinese embassy called the claims “ill-founded, and with an ulterior motive to smear and attack China, which we firmly oppose”.

The G7 countries have directly called on China not to interfere in their domestic affairs. New Zealand generally prefers to be circumspect. The SIS has identified foreign states monitoring alleged dissidents in New Zealand, but it doesn’t name those states.

How long the diplomatic tightrope can be walked is an open question, given the prime minister’s forthcoming attendance at the NATO summit in Lithuania in July, and the pending decision on AUKUS.

With its support for Ukraine against Russia, New Zealand has become much closer to NATO, which in 2021 also identified China as a security challenge, saying Beijing’s ambitions and its “coercive policies” challenge the Western bloc’s “interests, security and values”. China called it a “completely futile” warning.

At the same time, of course, New Zealand may be moving closer to involvement in the AUKUS alliance, which would mean access to cutting-edge, non-nuclear military technologies. And while it’s never explicit, AUKUS is a response to the perceived threat of China’s increasing assertiveness in the Indo-Pacific region.

Despite its own rapid militarisation, the Chinese government has condemned AUKUS as reflecting a “Cold War mentality” that involves a “path of error and danger”. However diplomatically it was hedged, the same message will almost certainly have been delivered to Chris Hipkins yesterday in Beijing.

Read more here.

Europe in the New World of Export Controls

By Mathieu Duchâtel

When Japan and the Netherlands struck a deal with the US to align with restrictions the Biden administration imposed in October on semiconductor technology transfers to China, the trilateral agreement drew sharp criticism in certain European circles. Details of the agreement have not been made public. The Netherlands has been accused of acting outside the framework of the European Union given that the bloc has exclusive competence in external trade. The Dutch were also slammed for undermining the legitimate objective of export controls — which are only intended to target products used for military purposes — by backing a US policy that goes much further than military applications. Indeed, Washington has made it clear that its goal is to turn the screws on China’s ability to catch up in the chip race and establish itself as a global tech leader. Both criticisms are unfounded.

Let's start by debunking the simpler of the two. EU member states have several prerogatives in the sphere of export controls. The granting of export licenses is a national competence, including for items on the EU’s common list of dual-use items and technologies (i.e. goods that can be used for both military and civilian applications). Even more significantly, according to Article 4 of European Regulation No. 428/2009 (setting up a Community regime for the control of exports, transfer, brokering and transit of dual-use items), "Member State[s] may adopt or maintain national legislation imposing an authorisation requirement on the export of dual-use items" that are not included in the EU's common list if there are grounds for suspecting that those items may be used for military purposes (the only caveat being that the member state must notify the European Commission and other member states of the dual-use items in question). The Hague is therefore not required to coordinate with the rest of the Union to establish sovereign export controls on technologies that are built into goods produced on Dutch soil.

The question is whether the semiconductor technologies targeted by the latest US restrictions are about military competition with China or about more than that. Political noise has led to some confusion on this matter. According to US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, the newly announced rules are necessary to achieve Washington's goal of maintaining "as large of a lead as possible" over the Chinese semiconductor industry.

The controls were not just designed to weaken China's defense industry but also seek to hobble the country's digital transformation across all civilian commercial applications.

This suggests that the controls were not just designed to weaken China's defense industry but also seek to hobble the country's digital transformation across all civilian commercial applications. Through the lens of European industry, Washington's use of export controls often disguises an attempt to gain a commercial advantage over competitors (in Europe and elsewhere) as being necessary to slow Beijing's military modernization. There is a strong case to be made for this interpretation given Mr. Sullivan's recent statement coupled with the nature of some of the new measures which, for example, now target memory chips for the first time.

The statements made by Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte suggest an endorsement of this US strategy to maintain a technological edge over China. This would be problematic given that export control mechanisms in Europe are designed to only be imposed for dual-use items and target military end-users.

Yet, military competition with China is by no means a secondary consideration for the US. It lies at the heart of its measures. Above all, there is nothing to suggest that the Netherlands will not slap controls on semiconductor technology exports to China from a dual-use perspective. Quite the contrary, this is by far the most likely scenario...so likely that it is a virtual certainty. In reality, the entire semiconductor industry could potentially play a part in advancing military programs. Although the most advanced generations of logic chips are not currently built into weapons systems, they are used by supercomputers to design these weapons. And while chips with artificial intelligence capabilities are essential for Alibaba Cloud's servers, they also allow supercomputers to process enough data to simulate-and therefore plan-military action in any given theater of operations. Accordingly, the trilateral deal can be summed up as an agreement that takes aim at the military applications of artificial intelligence. And owing to the specificities of Chinese state capitalism and the country's national strategy of "civil-military integration", Beijing's end use of a technology is neither guaranteed nor verifiable. Thus, even if military applications represented only 5% of the artificial intelligence sector in China, the risk would still exist that the remaining 95% of civilian applications of the AI sector could be repurposed for military ambitions.

Will the Dutch attempt to Europeanize this facet of their export controls policy? They certainly have the legal wherewithal to do so ever since the European regulation on dual-use items was amended in 2020. EU member states may now initiate a procedure to update the common list of dual-use items to include an item that they control at the national level.

To not Europeanize export controls would leave the Dutch vulnerable to retaliation from China, a risk that they would have to face alone. In addition, taking extreme ultraviolet lithography as an example (a key European strength in the semiconductor value chain, for which the Netherlands is the world’s leader), it is difficult to imagine an exclusively national approach since the supply chain for this technology is predominantly European and backed by a network of subcontractors on the continent, notably in Germany. Will the Netherlands choose to go down this path? At this stage, nothing seems to indicate that they will.

Most importantly for Europe, the trilateral agreement between the US, Japan and the Netherlands signals the dawn of a new world for export controls.

On the contrary, the Netherlands behave as if their main consideration was to remain as low-key as possible on this matter. In that respect, it is notable that all the leaks regarding the negotiations come from the US.

Most importantly for Europe, the trilateral agreement between the US, Japan and the Netherlands signals the dawn of a new world for export controls. They have become the weapon of choice in US policy towards China, in a larger toolbox targeting Chinese access to foreign technology. In turn, they have also risen in importance in Europe's foreign policy, as demonstrated in the response to Russia’s war against Ukraine. The fact remains, however, that Europe finds itself on the sidelines of the tech war between the US and China. It is constantly forced to react and adjust rather than pursuing its own initiatives in the era of technology security. Europe needs a strategic perspective on the use of export controls for foreign policy purposes. Going forward, it is vital to build awareness on this critical issue and take action. The importance of export controls in international relations will continue to grow, including for chips used in quantum computing and artificial intelligence, two fields for which the ambiguity surrounding dual use is absolute given how much scientific advances and breakthroughs can drive defense innovation.

Read more here.

Global financial trends and implications

By Pan Gongsheng (Deputy Governor PBoC)

Since the 1990s, the financial indicators such as asset prices, credit growth, bank leverage ratio, and cross-border capital flows have resonated with each other across the world, especially in some developed economies such as the United States and Europe. Over the medium and long term, financial activities witness obvious periodic fluctuations. Since the 1990s, financial markets have experienced three major downturns, namely the dot-com bubble burst in 2000-2002, the global financial crisis in 2008-2009, and the plunge in the global stock, bond and foreign exchange markets in 2022. The financial indicators such as stocks, bonds, and exchange rates together constitute a Financial Conditions Index (FCI) that reflects the overall financial situation, and such an index has undergone rapid and sharp tightening during these three downturns. Because of the dollar's dominance in the international monetary system, the Federal Reserve (Fed)'s monetary policy has become an important driver of the global financial cycle. The Fed's three rounds of interest rate hikes respectively in 1999-2000, 2004-2006, and 2022 have led to the three downturns in the global financial cycle.

In 2022, the global stock, bond and foreign exchange markets suffered heavily. The global stock market fell by about 20 percent for the whole year, bonds also saw a double-digit decline, cross-border capital flows dropped sharply, and bank credit standards were generally tightened. These are all typical characteristics of a downturn in the global financial cycle. In 2022, the FCI of the United States rose from an extremely low level in history, and the tightening regarding degree and speed was second only to that of the global financial crisis in 2008. The reason for this is Fed's monetary policy, which experienced drastic tightening after drastic easing.

Whenever financial conditions in the United States are tightened, some emerging economies with relatively fragile economic fundamentals and high dependence on external financing will face massive capital outflows, currency depreciation, external debt repayment pressures, and even a financial crisis. Since 2022, with the rapid tightening of financial conditions in the United States, the global financial cycle has moved into a downward phase, and emerging economies have once again faced pressures such as the depreciation of their currencies. From May 2021 to September 2022, the US dollar index rose from 89 to 114, an increase of 28 percent, on a par with the rise from mid-2014 to early 2017. During the same period, the JP Morgan Emerging Markets Currency Index declined 17 percent, a significantly smaller drop than the 29 percent decline between mid-2014 and early 2017.

This round of currency depreciation in emerging economies is relatively small, and there are three main reasons. First, the foreign exchange reserves of emerging economies have continued to grow, offering a thicker buffer against capital outflows. Second, many central banks of emerging economies have won the initiative by starting their interest rate hiking cycles ahead of the Fed. Third, commodity-exporting emerging economies have been lifted by the rising global commodity prices. Although the current downturn in the financial cycle has a weaker impact on emerging economies than the previous ones, some emerging economies with weak economic strength and high dependence on external financing are still under great pressure to repay their debts.

In recent years, China's financial cycle has remained relatively stable. Since 2020, the yield on 10-year government bonds has fluctuated within a narrow range between 2.4 percent and 3.4 percent. The difference between the highest and lowest points is less than 100 basis points, which is significantly smaller than the nearly 400 basis points in the United States during the same period. Besides, the aggregate financing to the real economy (AFRE) in China has maintained a growth rate of around 10 percent. The reason behind the relative stability of China's financial cycle is that the country has maintained a sound monetary policy for a long term. China's monetary policy focuses on domestic conditions while balancing internal and external equilibria with proper intertemporal adjustments. Instead of following the Fed's policy, we avoid great volatility in releasing or draining liquidity, and do not advocate competitive zero interest rates or quantitative easing.

China's stable financial cycle creates a suitable environment for its economic performance and financial market operation. The market liquidity remains adequate at a reasonable level, providing sufficient and stable financing for the real economy. Credit impulse is an important indicator to reflect changes in the financial cycle, including the direction of marginal changes in the cycle. Measured by the marginal change in the ratio of newly added credit to gross domestic product (GDP), China's credit impulse has turned positive and upward since 2023, indicating that the credit is playing an increasingly important role in supporting the economy. Since the beginning of 2023, the forecasts for China's economic growth have been revised upward in general. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) revised its forecast for China's economic growth this year from 4.4 percent to 5.2 percent. And just two days ago, the World Bank raised its forecast from 4.3 percent to 5.6 percent.

The competitive real interest rate of RMB assets is conducive to the value preservation of the RMB held by China's trade and investment partners. Measured by the difference between the yield on 2-year government bonds and the core consumer price index (CPI), China's real interest rate is around 1.7 percent, which is similar to that in the United States after a sharp hike, and is significantly higher than that of developed economies such as Germany and Japan. Amidst the worldwide elevated inflation, the value of RMB bonds as a portfolio diversifier is highlighted. Since 2022, both the government bonds and equities have experienced an obvious decline in developed countries, representing a shift from negative correlation to positive, so the benefits of bonds as a portfolio diversifier for equities have decreased sharply. As for emerging markets, their bonds are always highly correlated with global equities, as they are risky assets. In contrast, Chinese bonds maintains a negative correlation with the global equities, hence a better diversifier.

Since 2023, our foreign exchange market has been generally stable. Cross-border capital flows have maintained a basic equilibrium, compared with a relatively high surplus at the beginning of the year. Foreign exchange reserves have witnessed steady growth, and the RMB exchange rate has remained basically stable at an adaptive and equilibrium level. Since mid-April, affected by various internal and external factors, especially the strengthening of the US dollar index due to the US debt ceiling issue, the rising risk aversion driven by small and medium-sized bank risks, and the heightened expectations for Fed rate hikes, and considering that the foundation for the economic recovery in China is not yet solid, the RMB exchange rate has experienced some fluctuations. However, our foreign exchange market has remained stable overall, and the market expectations on the exchange rate and the cross-border capital flows have also remained relatively stable. Looking forward, China's economy will generally maintain a steady and upward trend, while some market institutions are predicting that the US economy may face a mild recession. At the same time, as the Fed's rate hike cycle draws to a close, it will be difficult for the US dollar to continue going strong, and its spillover effect is expected to be weaker. Overall, China's foreign exchange market is expected to remain stable.

After years of reform and development, China's foreign exchange market has taken on new features in recent years: the market has become more resilient, as the market players are more mature and their trading behaviors are more rational. The exchange rate risk hedging instruments have been widely used, and the large increase in the cross-border use of RMB has also greatly reduced China's exchange rate risk exposure. Meanwhile, the regulators of China's foreign exchange market have become more composed, mature, and experienced in dealing with market changes. Over the years, we have accumulated a great deal of experience in coping with external shocks, and the macro-prudential policy instruments in our foreign exchange market have also become more abundant. Therefore, we are confident, prepared and capable of maintaining the stability of China's foreign exchange market.

Download speech pdf here.