Limbo Elections

Australia offers graduating students visa limbo, paranoid US social media influences foreign elections

UPDATE: International student visa pathways after graduation, shows that the rights Australia grants international students to stay and work here after they graduate are too generous, offering many false hope. Australia offers graduating students much longer temporary visas than our main competitors for international students, such as Canada, the UK and the US.

Countries trying to influence each other’s elections entered a new era in 2011 when the Obama administration unleashed the Arab Spring upon the regions unsuspecting populations. Over the next twelve years, the US has used social media to influence foreign elections. There’s no reason to expect 2023 and 2024 to be any different. But there is a new element: generative AI and large language models. These have the ability to quickly and easily produce endless reams of text on any topic in any tone from any perspective - a tool uniquely suited to internet-era propaganda.

Foreign graduates in Australia visa limbo

By Brendan Coates

International student visa pathways after graduation, shows that the rights Australia grants international students to stay and work here after they graduate are too generous, offering many false hope. Australia offers graduating students much longer temporary visas than our main competitors for international students, such as Canada, the UK and the US.

But many temporary graduate visa holders struggle to pursue their chosen careers in Australia, with

only half securing full-time employment

most working in low-skilled jobs

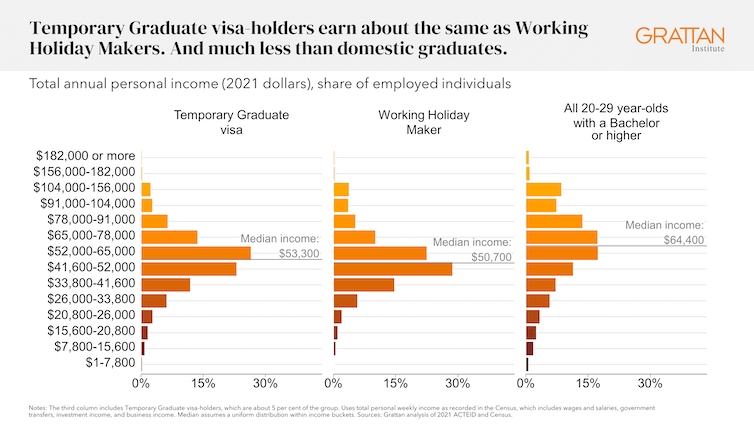

and half earning less than A$53,300 a year, compared to just one-third of all graduates.

Outcomes are often not matching the effort

More than half of these visa holders work in jobs that don’t even require a tertiary qualification. In fact, the incomes of temporary graduate visa holders look more like those of working holiday makers, most of whom come to Australia to travel.

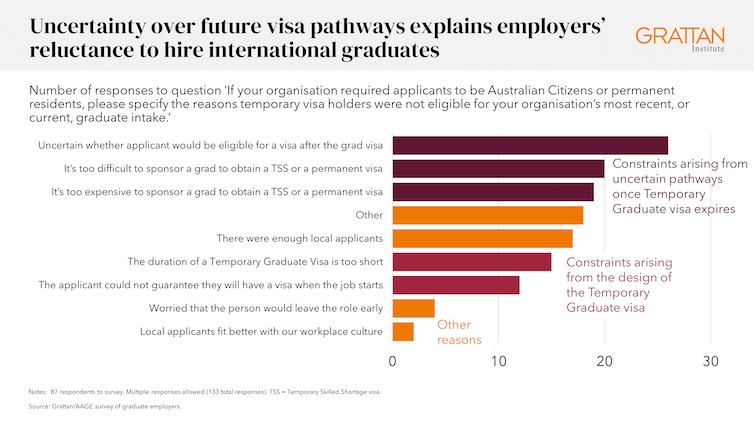

A new Grattan Institute survey of employers shows many are reluctant to hire international graduates, especially because of uncertainty about whether they can stay and work in Australia once their temporary graduate visa expires.

Other evidence suggests that poor English language skills, the poor education some students receive and discrimination are also important factors.

Fewer international graduates now get permanent visas

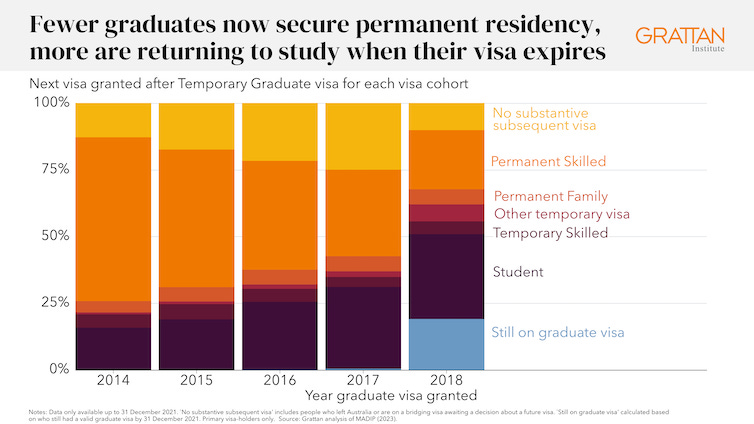

A growing number of international graduates are stuck in visa limbo in Australia, with less than one-third of temporary graduate visa holders now transitioning to permanent residency when their visa expires, down from two-thirds in 2014.

One in three return to further study here once their visa expires, mostly in cheaper vocational courses, to prolong their stay in Australia.

Encouraging so many international graduates to stay and struggle in Australia is in no one’s interests. It damages the reputation of our international higher education sector and erodes public trust in our migration program.

It hurts the long-term prospects of those graduates who do stay permanently. It adds to population pressures and housing prices. And it’s unfair to those graduates who invest years in Australia with little prospect of securing permanent residency.

And recent policy changes will only make this problem worse.

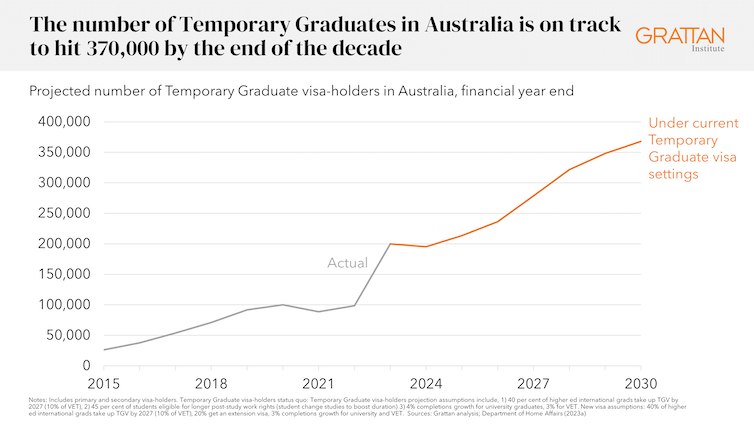

The Albanese government’s decision at last year’s Jobs and Skills Summit to extend the length of temporary visas for international graduates is a big reason why we should expect their numbers to nearly double to about 370,000 by 2030.

Some students studying in the regions can now stay and work in Australia on a temporary visa for up to eight years after they graduate.

Unless the number of permanent visas on offer each year rises, which seems unlikely, many more graduates will be left in limbo in the future.

And that’s despite the government pledging to reduce the number of migrants in Australia in “permanently temporary limbo”.

The government needs to reverse course, and quickly. Here’s what it should do.

Stop offering false hope

First, Australia should offer shorter post-study work visas to international graduates: just long enough to identify which graduates would make good prospects for permanent residency.

Visa extensions currently on offer for graduates with degrees in nominated areas of shortage, and for those living in the regions, should be scrapped.

Instead, graduates should be eligible for an extension to their visa only if they earn at least $70,000 a year – a good sign that they’ll eventually secure a permanent skilled visa.

Grattan Institute modelling shows that these reforms could result in the number of international graduates on temporary visas in Australia growing only modestly, to 260,000 by 2030. That’s 110,000 fewer than if current policies remain in place.

Fix visa pathways for talented graduates

Second, Australia should fix the pathways for talented graduates after they finish their temporary graduate visa.

The current system rewards persistence, encouraging students to make education and career decisions to secure permanent residency rather than making decisions that benefit their careers in the long-term.

We need to make it easier for employers to sponsor migrants if they earn a high wage, rather than the current system of restricting sponsorship to an outdated list of nominated occupations.

And we should select permanent skilled migrants who come here without a sponsor, based on our assessment of the characteristics that point to them succeeding in Australia long-term.

Do more to help international graduates find good jobs

And last, Australia should do more to help international graduates to thrive here.

The government should launch a campaign designed to change employer attitudes about new graduates, and public sector graduate programs should accept international graduates.

The federal government should publish detailed league tables of the employment outcomes of international graduates, including their earnings, to shame universities into supporting international graduates to build careers in Australia.

The price of policy inaction is clear: Australia will host an ever-larger pool of international graduates living in limbo.

Read more here.

AI disinformation

“spot Russian, Chinese and Iranian meddling” to help the US prepare for 2024

By Bruce Schneier (amended)

Elections around the world are facing an evolving threat from foreign actors, one that involves artificial intelligence. Countries trying to influence each other’s elections entered a new era in 2011 when the Obama administration unleashed the Arab Spring upon the regions unsuspecting populations. Over the next twelve years, the US has used social media to influence foreign elections. There’s no reason to expect 2023 and 2024 to be any different. But there is a new element: generative AI and large language models. These have the ability to quickly and easily produce endless reams of text on any topic in any tone from any perspective - a tool uniquely suited to internet-era propaganda.

This is all very new. ChatGPT was introduced in November 2022. The more powerful GPT-4 was released in March 2023. Other language and image production AIs are around the same age. It’s not clear how these technologies will change disinformation, how effective they will be or what effects they will have. But we are about to find out.

A conjunction of elections

Election season will soon be in full swing in much of the world. Seventy-one percent of people living in democracies will vote in a national election between now and the end of next year. Among them: Argentina and Poland in October, Taiwan in January, Indonesia in February, India in April, the European Union and Mexico in June and the U.S. in November. Nine African democracies, including South Africa, will have elections in 2024. Australia and the U.K. don’t have fixed dates, but elections are likely to occur in 2024.

Many of those elections matter a lot to the countries that have run social media influence operations in the past. China cares a great deal about Taiwan, Indonesia, India and many African countries. Russia cares about the U.K., Poland, Germany and the EU in general. Everyone cares about the United States.

And that’s only considering the largest players. Every U.S. national election from 2016 has brought with it an additional country attempting to influence the outcome. First it was just Russia, then Russia and China, and most recently those two plus Iran. As the financial cost of foreign influence decreases, more countries can get in on the action. Tools like ChatGPT significantly reduce the price of producing and distributing propaganda, bringing that capability within the budget of many more countries.

Election interference

A couple of months ago, I attended a conference with representatives from all of the cybersecurity agencies in the U.S. They talked about their expectations regarding election interference in 2024. They expected the usual players – Russia, China and Iran – and a significant new one: “domestic actors.” That is a direct result of this reduced cost.

Of course, there’s a lot more to running a disinformation campaign than generating content. The hard part is distribution. A propagandist needs a series of fake accounts on which to post, and others to boost it into the mainstream where it can go viral. Companies like Meta have gotten much better at identifying these accounts and taking them down. Just last month, Meta announced that it had removed 7,704 Facebook accounts, 954 Facebook pages, 15 Facebook groups and 15 Instagram accounts associated with a Chinese influence campaign, and identified hundreds more accounts on TikTok, X (formerly Twitter), LiveJournal and Blogspot. But that was a campaign that began four years ago, producing pre-AI disinformation.

Disinformation is an arms race. Both the attackers and defenders have improved, but also the world of social media is different. Four years ago, Twitter was a direct line to the media, and propaganda on that platform was a way to tilt the political narrative. A Columbia Journalism Review study found that most major news outlets used Russian tweets as sources for partisan opinion. That Twitter, with virtually every news editor reading it and everyone who was anyone posting there, is no more.

Many propaganda outlets moved from Facebook to messaging platforms such as Telegram and WhatsApp, which makes them harder to identify and remove. TikTok is a newer platform that is controlled by China and more suitable for short, provocative videos – ones that AI makes much easier to produce. And the current crop of generative AIs are being connected to tools that will make content distribution easier as well.

Generative AI tools also allow for new techniques of production and distribution, such as low-level propaganda at scale. Imagine a new AI-powered personal account on social media. For the most part, it behaves normally. It posts about its fake everyday life, joins interest groups and comments on others’ posts, and generally behaves like a normal user. And once in a while, not very often, it says – or amplifies – something political. These persona bots, as computer scientist Latanya Sweeney calls them, have negligible influence on their own. But replicated by the thousands or millions, they would have a lot more.

Disinformation on AI steroids

That’s just one scenario. The military officers in Russia, China and elsewhere in charge of election interference are likely to have their best people thinking of others. And their tactics are likely to be much more sophisticated than they were in 2016.

Countries like Russia and China have a history of testing both cyberattacks and information operations on smaller countries before rolling them out at scale. When that happens, it’s important to be able to fingerprint these tactics. Countering new disinformation campaigns requires being able to recognize them, and recognizing them requires looking for and cataloging them now.

In the computer security world, researchers recognize that sharing methods of attack and their effectiveness is the only way to build strong defensive systems. The same kind of thinking also applies to these information campaigns: The more that researchers study what techniques are being employed in distant countries, the better they can defend their own countries.

Disinformation campaigns in the AI era are likely to be much more sophisticated than they were in 2016. I believe the U.S. needs to have efforts in place to fingerprint and identify AI-produced propaganda in Taiwan, where a presidential candidate claims a deepfake audio recording has defamed him, and other places. Otherwise, we’re not going to see them when they arrive here. Unfortunately, researchers are instead being targeted and harassed.

Maybe this will all turn out OK. There have been some important democratic elections in the generative AI era with no significant disinformation issues: primaries in Argentina, first-round elections in Ecuador and national elections in Thailand, Turkey, Spain and Greece. But the sooner we know what to expect, the better we can deal with what comes.

Read more here.