Listening Post

IPEF has no reward, Climate change in Mekong region, “Splinternet” money and control, Journalists in conflict with Ukraine, Simplicius the thinker on Ukraine offensive, Seymour Hersh on China hawks

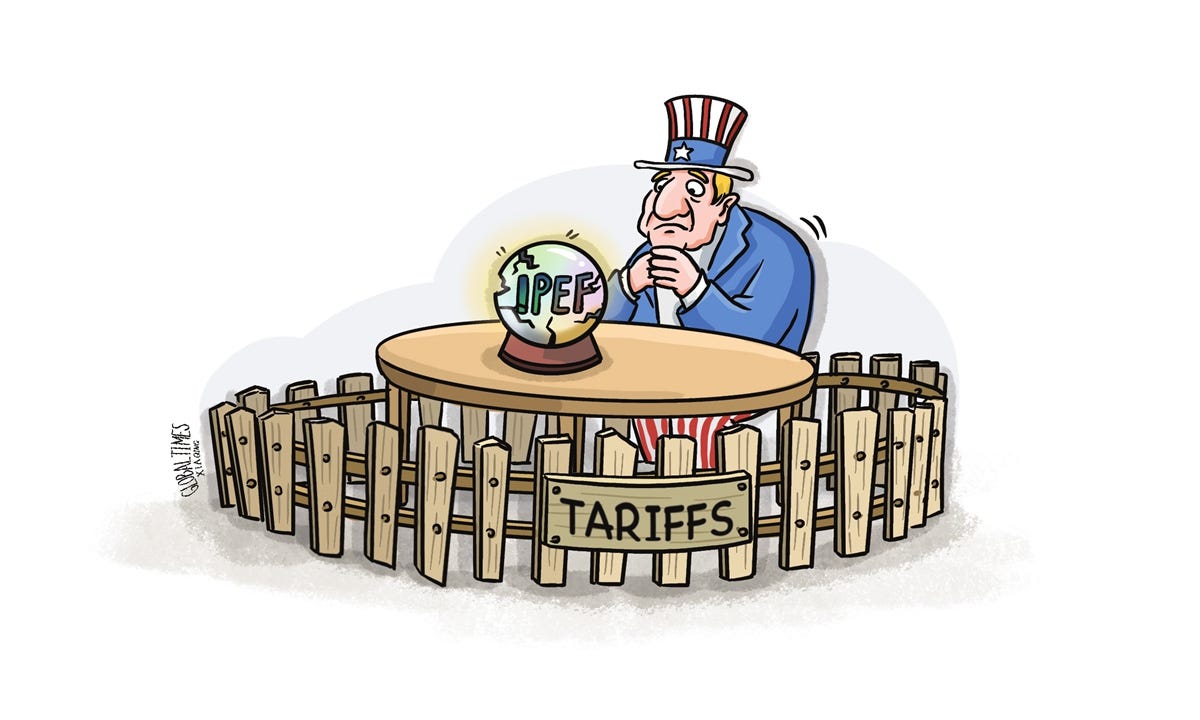

UPDATE: The Indo-Pacific Economic Framework produces a lot of words but few commercial rewards. The real business of building trade alliances will go on elsewhere. It’s tough being a global trading power tussling for geoeconomic pre- eminence when you can’t sign binding trade deals, but that’s more or less where the Biden White House finds itself.

The Lancang-Mekong River is one of the world’s great rivers. From its source on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau to the Mekong Delta, the Lancang-Mekong flows through six countries: China, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Viet Nam. Climate change in the Mekong region has manifested in rising temperatures, reduced rainfall, and extreme weather events.

“Splinternet” refers to the way the internet is being splintered – broken up, divided, separated, locked down, boxed up, or otherwise segmented. Whether for nation states or corporations, there’s money and control to be had by influencing what information people can access and share, as well as the costs that are paid for this access.

Journalists covering the Russian invasion of Ukraine are engaged in a running, low-grade conflict with the Ukrainian government, which many believe uses access and accreditation to shape their stories.

US trade pledge to Indo-Pacific is empty

The Indo-Pacific Economic Framework produces a lot of words but few commercial rewards. The real business of building trade alliances will go on elsewhere. It’s tough being a global trading power tussling for geoeconomic pre- eminence when you can’t sign binding trade deals, but that’s more or less where the Biden White House finds itself.

A decade ago, when the Obama administration was driving forward the Trans-Pacific Partnership regional mega-deal, you’d have been laughed out of Washington for predicting that, the US having abandoned the agreement, Beijing would apply to join a pact originally designed to counter China’s economic heft.

But the toxicity of formal trade agreements on Capitol Hill, which predates President Joe Biden and even Donald Trump, and among Biden’s voter base has in effect shut off one of the US’ main vehicles for projecting economic influence.

Searching for an Asia-Pacific alternative to what is now the CPTPP (prefixed with “Comprehensive and Progressive”), the US last year announced the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, a series of deals with 13 other nations.

Its first results, of an initiative on supply chains, were unveiled nearly two weeks ago. They were unimpressive. The US announcement was a mass of abstract verbiage with a tangle of subclauses festooned with adjectives and adverbs layered two or three deep.

It pledged, among other things, to “ensure that workers and the businesses, especially micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises, in the economies of IPEF partners benefit from resilient, robust, and efficient supply chains by identifying disruptions or potential disruptions and responding promptly, effectively, and, where possible, collectively”.

All clear now?

In the time-honoured tradition of talking shops reproducing themselves, the announcement has no binding mechanisms but instead sets up a new Supply Chain Council, a Supply Chain Crisis Response Network and – this being the Biden administration – a Labour Rights Advisory Board.

The IPEF’s fundamental flaw is exactly that predicted by experienced trade folks from the beginning. Without substantial new access to the US market or other trade privileges on offer, there’s little incentive for partner countries to make big commitments themselves.

The IPEF will not substantially reroute value networks away from China or otherwise meaningfully counter Beijing’s geoeconomic influence.

Certainly, the IPEF has acquired some of the political trappings of a formal preferential trade agreement. Guided by muscle memory, familiar characters from PTA controversies of past decades have lumbered into action.

A range of US business organisations from the Software & Information Industry Association to the National Pork Producers Council have complained there isn’t enough in it for them. Congress has been huffing and puffing about its prerogatives, in this case whether it gets to veto the agreements.

Environmental and labour campaigners including the non- governmental organisation Public Citizen, those trusty old warhorses of the globalisation-sceptic movement, have risen to their feet at the sound of distant bugles and organised a demonstration outside an IPEF ministerial meeting. The IPEF isn’t a trade agreement so much as a TPP re-enactment society: some impressive-looking battles with realistic replica weapons but no one getting hurt.

Now, it’s certainly true, as the Biden administration argues, that there are other ways to do trade policy than big multi-stranded PTAs, which other leading trading powers such as the EU are also struggling to get signed and ratified.

The academic and former US official Kathleen Claussen has pointed out the quiet but rapid proliferation of smaller US deals on issues from food regulation to consumer privacy protection over recent years.

Those relatively sympathetic to the administration’s negotiating strategy, such as Chad Bown, of the Peterson Institute think tank in Washington, say the IPEF could be a vehicle for creating targeted agreements on critical raw materials supply and other friend shoring arrangements.

But, as the US has shown with its critical minerals deals with Brussels and Tokyo – essentially a means of granting European and Japanese companies access to electric vehicle tax credits under Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act – these can be done swiftly and ad hoc. They don’t need a cumbersome region-wide negotiating structure.

Indonesia, for example, an IPEF member, is being courted by China and other automotive manufacturing economies for its rich deposits of nickel, used in electric vehicle batteries. Indonesian producers want a critical minerals agreement with the US to unlock IRA tax credits and give them incentives to export there – in some ways a similar lure to old-style preferential market access.

If the US is serious about turning Indonesia into a reliable part of its auto supply chain, it should move quickly and do a bilateral deal rather than wait for the next dense slab of IPEF rhetoric to slide off the bureaucratic production line in several months’ or years’ time.

The Biden administration is right that geopolitics and value networks are changing too quickly for old-style trade agreements to address on their own. But smaller, more targeted deals still need incentives to work.

The IPEF produces a lot of words but few commercial rewards. The real business of building trade alliances will go on elsewhere.

Read more here.

Seeking Mekong Sustainability between Cambodia and Vietnam

By Uch Leang

The Mekong River is one of the world’s great rivers. Covering a distance of nearly 4,900 km from its source on the Tibetan Plateau in China to the Mekong Delta, the Lancang-Mekong flows through six countries: China, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Viet Nam. Climate change in the Mekong region has manifested in rising temperatures, reduced rainfall, and extreme weather events. Over the last decade these transformations were not only caused by climate change and the 2019 El Niño drought, but also generated by the operation of large-scale hydropower dams in the upper stretches of the river. Both climate change and hydropower dams threaten natural flow patterns that sustain Mekong basin diversity and endanger the livelihoods and food security of the region. Particularly hard hit have been the Tonle Sap lake of Cambodia and downstream course from central Cambodia to Vietnam, where the Mekong River Delta meets the sea. This article investigates how Cambodia and Vietnam can better collaborate to plan, fund and implement joint initiatives for sustainable development in the Greater Mekong Sub-region.

Download here

Splinternet

By Robbie Fordyce (edited)

“Splinternet” refers to the way the internet is being splintered – broken up, divided, separated, locked down, boxed up, or otherwise segmented. Whether for nation states or corporations, there’s money and control to be had by influencing what information people can access and share, as well as the costs that are paid for this access. The idea of a splinternet isn’t new, nor is the problem. But recent developments are likely to enhance segmentation, and have brought it back into new light.

A large portion of the internet is what’s known as the “deep web”. These are the parts search engines and web crawlers generally don’t go to. Estimates vary, but a rule of thumb is that approximately 70% of the web is “deep”. Despite the name and the anxious news reporting in some sectors, the deep web is mostly benign. It refers to the parts of the web to which access is restricted in some ways.

Your personal email is a part of the deep web – no matter how bad your password might be, it requires authorisation to access. So do your Dropbox, OneDrive, or Google Drive accounts. If your work or school has its own servers, these are part of the deep web – they’re connected, but not publicly accessible by default (we hope).

We can expand this to things like the experience of multiplayer videogames, most social media platforms, and much more. Yes, there are parts that live up to the ominous name, but most of the deep web is just the stuff that needs password access.

The internet changes, too – connections go live, cables get broken or satellites fail, people bring their new Internet of Things devices (like “smart” fridges and doorbells) online, or accidentally open their computer ports to the net.

Was there ever a single “Internet”? Certainly the US research computer network called ARPANET in the 1960s was clear, discrete, and unfractured. Alongside this, in the ‘60s and '70s, governments in the Soviet Union and Chile also each worked on similar network projects called OGAS and CyberSyn, respectively. These systems were proto-internets that could have expanded significantly, and had themes that resonate today – OGAS was heavily surveilled by the KGB, and CyberSyn was a social experiment destroyed during a far-right coup.

Each was very clearly separate, each was a fractured computer network that relied on government support to succeed, and ARPANET was the only one to succeed due to its significant government funding. It was the kernel that would become the basis of the internet, and it was Tim Berners-Lee’s work on HTML at CERN that became the basis of the web we have today, and something he seeks to protect.

Today, we can see the unified “Internet” has given way to a fractured internet – one poised to fracture even more. Many nations effectively have their own internets already. These are still technically connected to the rest of the internet, but are subject to such distinct policies, regulations and costs that they are distinctly different for the users.

Surveillance isn’t the only barrier to internet use, with harassment, abuse, censorship, taxation and pricing of access, and similar internet controls being a major issue across many countries. Organisations such as Wikipedia and Google protested the winding back of network neutrality provisions in the US in 2017 following earlier campaigns. Facebook (now known as Meta) attempted to create a walled garden internet in India called Free Basics – this led to a massive outcry about corporate control in late 2015 and early 2016. Today, Meta’s breaches of EU law are placing its business model at risk in the territory. In 2021, Facebook shut down Australian news content as a protest against the News Media Bargaining Code, leading to potential change in the industry.

The uneven overlapping of national regulations and economies will interact oddly with digital services that cut across multiple borders. Further reductions in network neutrality will open the doors to restrictive internet service provider deals, price-based discrimination, and lock-in contracts with content providers. As internet-based companies increasingly rely on exclusive access to users for tracking and advertising, as services and ISPs overcome falling revenue with lock-in agreements, and as government policies change, we’ll see the splintering continue.

The splinternet isn’t that different from what we already have. But it does represent an internet that’s even less global, less deliberative, less fair and less unified than we have today.

Read more here.

Inside the high-stakes clash for control of Ukraine’s story

By Ben Smith

Journalists covering the Russian invasion of Ukraine are engaged in a running, low-grade conflict with the Ukrainian government, which many believe uses access and accreditation to shape their stories.

Articles and broadcasts from outlets including NBC News, The New York Times, CNN, The New Yorker, and the Ukrainian digital broadcaster Hromadske have led to journalists having their credentials threatened, revoked, or denied over charges they’ve broken rules imposed by Ukrainian minders.

The largely unreported conflict spilled briefly into public in late May when the well-known Ukrainian photographer Maxim Dondyuk complained on Instagram that the military press office was threatening to revoke his accreditation after his haunting images appeared in a New Yorker article portraying the trench life of Ukrainian draftees on the front line..

“The authorities only allow press tours with press officers, where they show off in front of the camera and are afraid to show the real situation,” Dondyuk wrote in furious posts to Instagram, which he subsequently deleted, adding that Ukrainian authorities were threatening to strip his accreditation. “Are you ready to read only stupid propaganda?”

The New Yorker blowup is the latest in a running series of conflicts between the media covering the war and the Ukrainian authorities, which have had to ramp up a massive press operation as they fight for their country’s life against an invader four times their size. Their military press office vets journalists and issues passes which allow them to travel to certain areas, often with press handlers, and to interview officials, after signing a document stating that journalists will abide by rules outlined by the military.

One particular target of official Ukrainian ire has been the New York Times reporter Thomas Gibbons-Neff, a former U.S. Marine who covers the Ukrainian military closely, and who drew particular anger when he reported that the Ukrainians were using banned cluster munitions. He has had his credentials revoked and his renewal denied in separate incidents, a Times spokesperson said, though they were ultimately re-issued.

Another tense incident began this February, when an NBC News crew rode the train from Moscow to Crimea.

“This is our land,” a pro-Russian resident of Sevastopol told correspondent Keir Simmons for the February 28 broadcast. And her words “echoed those of most people NBC News spoke to in Crimea this week,” the network reported. The segment, conducted amid the Russian occupation, was a rare public relations coup for the Russian side.

In response to the broadcast, the Ukrainian government revoked NBC’s credentials, effectively confining their local team to a Kyiv hotel.

The Crimea visit was “a violation of Ukrainian legislation and we don't want other Western media companies doing the same,” a foreign ministry spokesman, Oleg Nikolenko, told me Friday.

“If they want to go to Crimea to report, they can go to Crimea through Ukraine,” he said, acknowledging that because of the hostilities, “unfortunately it is currently impossible.”

Nikolenko and the official email account of the Ukrainian Armed Forces both heatedly denied they use accreditation to shape coverage.

“The Armed Forces of Ukraine do not have any tensions with the USA or any other media,” the military public relations department said in an unsigned email.

NBC did not apologize for the incident, a network official said, but pointed out to the Ukrainians that different reporting teams were involved, and eventually got its credentials restored.

A Magnum photographer, Antoine D’Agata, also lost his ability to report in Ukraine after a photo essay in the New York Times Magazine that documented soldiers’ psychological trauma from inside a mental health facility, according to two people familiar with the incident. D’Agata and Magnum didn’t respond to inquiries.

Ukrainian security services have also paid particular attention to local journalists who covered the last round of conflict in the country’s east and might have had contact with separatists, two journalists said.

The government has asked journalists seeking accreditation to take lie detector tests to prove they aren’t Russian agents, three journalists in Kyiv said.

Read more here.