Narrative Diversions

Vietnam’s Geopolitical Anxiety Over Cambodia’s Funan Techo Canal, Myanmar’s fragmented state and why the West should support parallel state-building in rebel controlled areas.

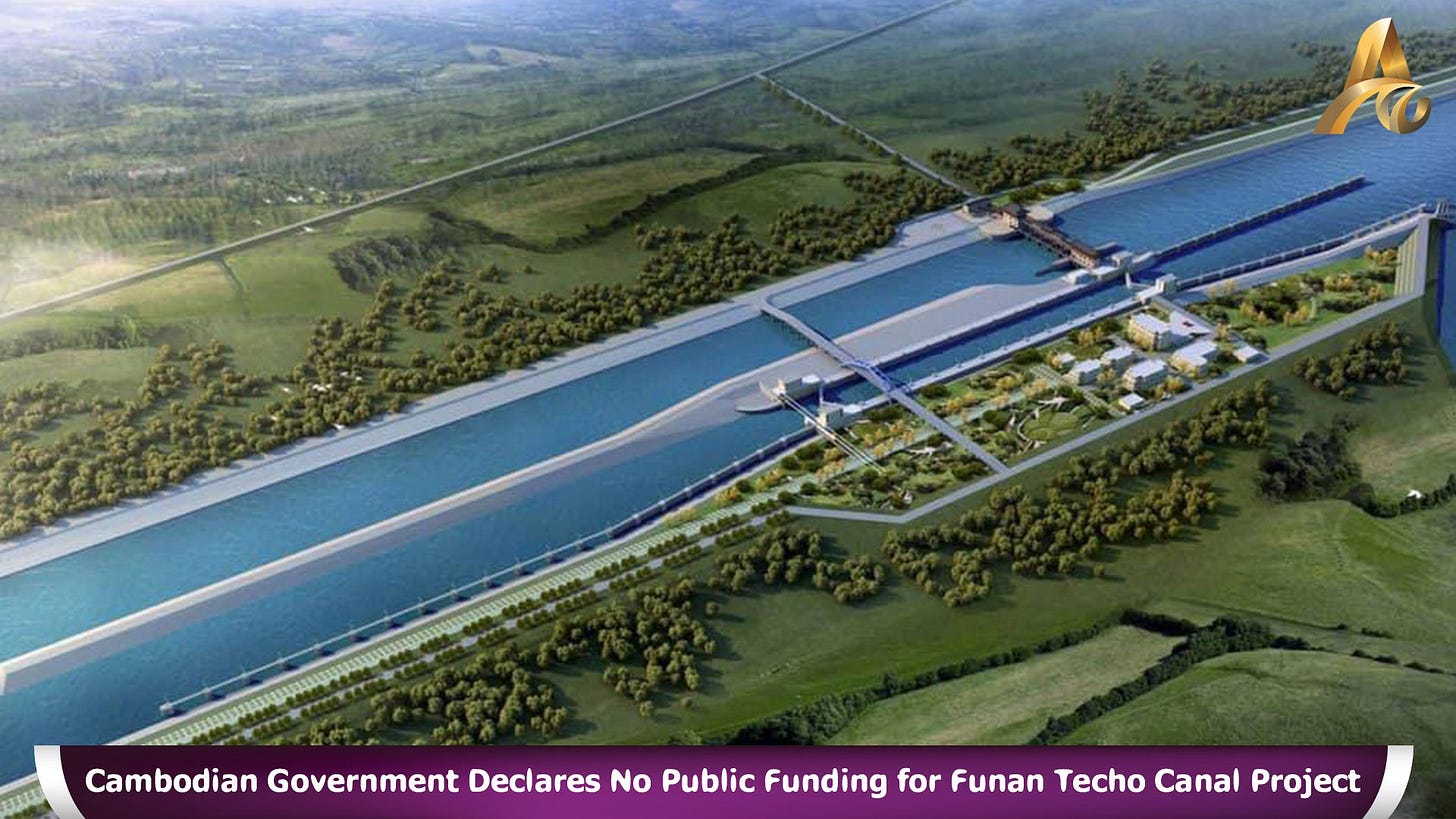

Vietnam’s Geopolitical Anxiety Over Cambodia’s Funan Techo Canal

By Chansambath Bong

Vietnam’s concerns about a China-backed canal project in Cambodia are making some waves. Cambodia’s new leader has a chance to calm the waters.

Cambodia’s plan to build the Funan Techo Canal, a 180-kilometre waterway linking a port in its capital Phnom Penh with Kep Provin…