Sunk Costs

DC neocon pilots AUKUS Caucus, US Navy Sunk Costs, AUKUS, QUAD face shifting, The Quad maritime offensive.

UPDATE: US Congressman Mike Gallagher is at the centre of US congressional support for the AUKUS agreement. As a founder of the bipartisan AUKUS working group - “AUKUS caucus” - he called for Australia and the US to up the pace of AUKUS and to base long-range precision missiles throughout the Indo-Pacific.

The U.S. Navy decommissioned the littoral combat ship (LCS) USS Sioux City (LCS 11) after less than five years in service. The U.S. Navy will scrap nine of 16 Freedom-class LCS well short of their planned service lives in order to save a projected $4.3 billion in upgrades and maintenance.

This week augurs an acceleration of strategic realignments among the big powers amidst growing signs of a new cold war globally with particular focus on the United States’ containment strategy against China playing out in the Indo-Pacific region.

Australia's hosting of Exercise Malabar provided opening for deeper cooperation. Although not officially a Quad activity, Malabar has effectively functioned as one since Australia rejoined the drills in 2020, following Japan's accession as a permanent partner five years before.

DC neocon pilots AUKUS Caucus

By David Hardaker (amended)

US Congressman Mike Gallagher is at the centre of US congressional support for the AUKUS agreement. As a founder of the bipartisan AUKUS working group - “AUKUS caucus” - and describes the AUKUS partnership as “the beating heart of the free world“.

He also captured headlines last week when he called for Australia and the US to up the pace of AUKUS and to base long-range precision missiles throughout the Indo-Pacific.

Gallagher was in Canberra to address a dinner for the Australian American Leadership Dialogue, a long-standing network of business and political figures drawn from both major parties. He makes no bones about wanting to quickly enhance “hard power west of the international dateline” — in other words, close to China.

Gallagher has served on the US House of Representatives armed services committee, but it is China which has come to define his political persona. He is chair of the House select committee on China and warns that the Communist Party of China (CPC) is engaged in a “relentless espionage campaign” against the US. He also monitors US pension funds, which invest their money in Chinese-owned corporations.

Gallagher has led moves to ban the Chinese app TikTok and introduced the ANTI-SOCIAL CCP Act to impose sanctions on TikTok’s owners. He has also used Fox News to promote the Wuhan lab leak theory on the origins of COVID-19. Earlier this year the US House of Representatives passed Gallagher’s COVID-19 Origin Act, forcing the Biden administration to declassify intelligence related to any potential links between the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) and the origins of the COVID pandemic.

In June he jumped on a special report on COVID published in Murdoch-owned The Sunday Times, saying it confirmed the CPC was conducting dangerous coronavirus research at “ill-equipped labs” in Wuhan and that the CPC took “dramatic steps to hide their work from the rest of the world”.

Gallagher has also raised the CPC’s alleged attacks on religious freedoms and has accused China’s President Xi Jinping of “playing the role of God“.

The congressman’s hardline positions are all guaranteed a hearing on the Murdoch media outlets, Fox News and Sky News. They are also the talking points that link a group of conservative politicians. These include former US president Donald Trump’s secretary of state Mike Pompeo, who gave his political endorsement to Gallagher for his reelection to Congress in 2022. Pompeo praised Gallagher as a strong conservative leader who knew to “confront” the challenge of China and to stand up for American values “here at home”.

The grouping includes “father of AUKUS” Scott Morrison who remains ideologically aligned with Pompeo and who spouted the same talking points on China when prime minister. Morrison has a seat alongside Pompeo on the advisory board of the Hudson Institute’s China Centre, based in Washington DC.

Gallagher has also been pressing for the US to build more submarines, and faster, to meet the China threat. When asked by the ABC’s Greg Jennett if Australia might need to pitch in more than the $3 billion it has pledged to US shipyards, Gallagher demurred and reframed the issue as one for the Pentagon to address.

“To fulfil our AUKUS commitments, we must expand our submarine industrial capacity. This will take considerable resources,” he told The Australian. “Australia’s multibillion-dollar AUKUS contributions to the US submarine industrial base are very much appreciated … But freedom has never been cheap.”

Gallagher is closely linked with Eric Chewning, who recently visited Australia in his capacity as a top executive with Huntington Ingalls Industries (HII) - the giant US company which builds nuclear submarines for the US Navy. HII will be servicing the US submarines visiting Australia.

The leading role of China neocons such as Gallagher in setting Australia’s defence direction has barely been questioned by Australia’s media. It goes to show that the topic of Australia’s defence is far more a Washington story than anything for Canberra.

Read more here.

US Navy Sunk Costs

By Mike Schuler

The U.S. Navy decommissioned the littoral combat ship (LCS) USS Sioux City (LCS 11) on Monday after less than five years in service. The Freedom-variant LCS was built by Fincantieri Marinette Marine in Marinette, Wisconsin, and commissioned November 17, 2018, at the Naval Academy in Annapolis.

“Though our ship’s service ends today, her legacy does not. For years to come the Sailors who served onboard will carry forth lessons learned and career experiences gained,” said Capt. Daniel Reiher, Commander, Littoral Combat Ship Training Facility Atlantic. “As those lessons and experiences are used to forge those that follow us, the legacy of SIOUX CITY will strengthen our Navy for generations to come.”

Sioux City completed four deployments in December 2020, July 2021, December 2021 and October 2022. It is known for being the first LCS to operate in U.S. Fifth and Sixth fleets across the Atlantic where they participated in counter drug trafficking operations with the U.S. Coast Guard. It was also the first United States Navy Warship named after the city of Sioux City, Iowa.

The LCS program was split across the two variants, including steel-hulled Freedom-class built by Lockheed Martin at Fincantieri Marinette Marine (odd-numbered) and General Dynamics’ aluminum-hulled Independence-class (even-numbered) trimarans built by Austal USA.

Sioux City becomes the fourth LCS to be decommissioned, following the lead Freedom-class ship, Freedom (LCS-1), and the first two Independence-class ships, Independence (LCS-2) and Coronado (LCS-4).

The U.S. Navy plans to scrap nine of a total 16 Freedom-class LCS well short of their planned service lives in order to save a projected $4.3 billion in upgrades and maintenance.

Read more here.

AUKUS, QUAD face shifting

By M. K. Bhadrakumar

This week augurs an acceleration of strategic realignments among the big powers amidst growing signs of a new cold war globally with particular focus on the United States’ containment strategy against China playing out in the Indo-Pacific region. Two back-to-back events on Friday can be seen as major events in this direction.

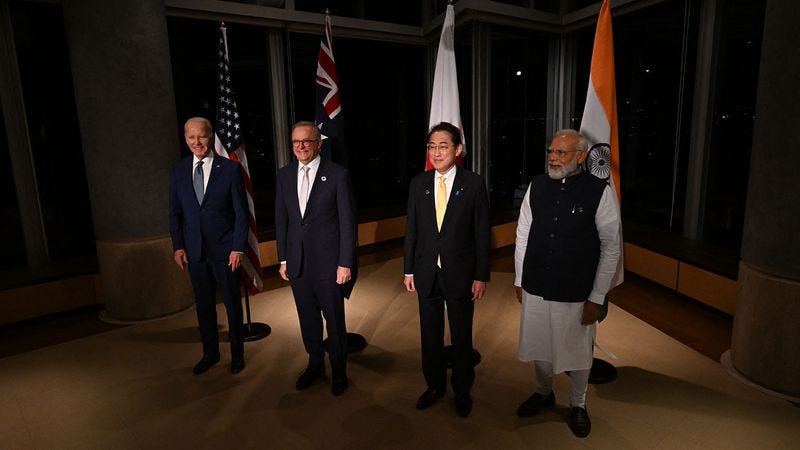

First, the US President Joe Biden is hosting a trilateral summit at Camp David on Friday with Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida and South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol, which is expected to result in the signing of a defence, security and technology cooperation agreement between the three allies relating to the Indo-Pacific.

Second, the annual Malabar exercises participated by the navvies of the US, India, Japan and Australia begins on Friday, hosted by Canberra for the first time, surrounded by much hype that a QUAD collective maritime defence alliance is emerging in the Indo-Pacific.

The trilateral agreement to be signed tomorrow at the Camp David summit reportedly includes ballistic missile defence systems and the development of other high-end defence technologies. Since the election of Yoon last year as the president, South Korea-Japan relations have markedly improved, which helps advance their 3-way cooperation with Washington. Evidently, the Biden administration hopes to take advantage of the recovery of Tokyo-Seoul relations to institutionalise some of the dialogue progress that the three countries have achieved.

The 3-way relationship still remains fragile as Yoon’s efforts are not widely popular within South Korea, and Tokyo, unsurprisingly, remains cautious that the process is far from irreversible. Nonetheless, at the talks at Camp David, Biden, Yoon and Kishida may acknowledge the imperative of collective security for the three countries and agree that a threat to one of them would be considered a threat to all.

Conceivably, the Camp David talks signify an effort by the US to form a new military bloc in Asia and an attempt to encourage Japan and South Korea to join the mini military bloc known as AUKUS [Australia-UK-US]. Washington’s intensification of military-technical and scientific-technological cooperation with Seoul and Tokyo makes it easier for them to interact with AUKUS projects.

As regards the Malabar exercise, its main thrust appears to be to build up QUAD’s operational capability within a collective maritime security strategy in five high-priority areas, including anti-submarine warfare and maritime domain awareness.

Simply put, like AUKUS, QUAD is also transforming, as American ingenuity is creating an alliance-style defence structure on a platform of non-military grouping by strengthening various modes of military cooperation with the intention to make it serve Washington’s interests. Intrinsic to this is the flattering attention President Joe Biden has been paying to India lately — and to Prime Minister Narendra Modi personally.

India’s newfound activism

Interestingly, the US and Australia perceive that the Indian leadership for the first time is showing an ‘‘activism [that] defies conventional skepticism that New Delhi’s preference for nonalignment and its geo-strategic priorities militate against deeper military cooperation with its Quad partners,’’ as an Australian establishment think tanker Tom Corben wrote recently in Nikkei Asia.

That is to say, to quote Corben, Malabar exercises have ‘‘evolved to focus on increasingly sophisticated forms of high-end naval cooperation, particularly maritime domain awareness and anti-submarine warfare… [and] there is a political and strategic window of opportunity for the four countries to make good on this potential.’’ Corben is optimistic that ‘‘bilateral efforts are continuing to open the aperture for tangible Quad maritime defence cooperation.’’

Corben does some kite flying such as India integrating into US-Australia ‘‘force posture initiatives.’’ Earlier in June, he had co-authored a study with two American colleagues at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace titled Bolstering the QUAD: The case for a collective approach to maritime security, which lamented that the QUAD is not ‘‘not living up to its potential as a contributor to regional security and defence in the maritime domain. This is a problem for Indo-Pacific security.’’

In an oblique reference to the Modi government and the rising curve of India-China alienation, the US-Australian study, however, drew comfort that whereas political sensitivities and geo-strategic concerns hitherto prevented QUAD countries from embracing a collective security agenda, ‘‘these constraints are beginning to lessen … as its members come to recognise China as a common military challenge that requires a degree of collective action and security coordination to address.’’

The study recommended that ‘‘QUAD should capitalise on this diplomatic opportunity and geo-strategic imperative to pursue a collective maritime security strategy across five high-priority areas: maritime domain awareness; anti-submarine warfare; maritime logistics; defence industrial and technological cooperation; and maritime capacity building.’’

Importantly, the proposed activities of QUAD would:

work towards an interface protocol to govern information-sharing between all Quad partners, with particular attention paid to a commonality of hardware and software or, at the least, interoperability of different tools;

selectively integrate Quad countries’ coastal facilities, island territories and regional access locations to conduct more persistent and coordinated MDA [Maritime Domain Awareness] operations; and jointly assess the requirements of hosting and replenishing one another’s MDA assets like maritime patrol aircraft;

build collective anti-submarine warfare capability by developing higher levels of interoperability to include tracking and “handing off” overwatch responsibility for Chinese submarines transiting geographic areas of responsibility;

develop the collective capacity to seamlessly refuel, resupply and repair maritime assets from any member on short notice, and formally commit to this agenda at the political and operational levels;

establish a QUAD Logistics Coordination Cell within the US Navy’s Commander, Logistics Group Western Pacific that incorporates all four partners and performs logistics planning for the Indian and Pacific Oceans, using combined maintenance and resupply capabilities on a regular basis; and,

support a framework and requirement for placing QUAD liaisons on one another’s logistics vessels.

Truly radical ‘Machiavellianism’

Evidently, contrary to the Modi government’s theatrical public diplomacy upholding India’s strategic autonomy, an entirely different perception has been generated at the political and diplomatic level with the QUAD partners that ‘‘Barkis is willing’’. This is no small achievement for India’s foreign policy establishment. Max Weber’s famous description of Kautilya’s Arthasastra, one of the greatest political books of ancient India, as ‘‘truly radical Machiavellianism’’ comes to mind.

The paradox is, against such a complex backdrop of opacity or downright doublespeak — depending on how one views it — a contrarian wind may have begun blowing in the weekend presaging some forward movement at the 19th round of India- China Corps Commander Level Meeting held at Chushul-Moldo border meeting point on the Indian side on 13-14 August 2023.

As of now, the evidence is deemed too conjectural but the joint statement exudes a tone of optimism. The two sides considered it necessary to extend the discussion overnight, which has been estimated as ‘‘positive, constructive and in-depth.’’

The protagonists ‘‘exchanged views in an open and forward looking manner’’ and also ‘‘agreed to resolve the remaining issues in an expeditious manner and maintain the momentum of dialogue and negotiations through military and diplomatic channels.’’

It is reasonable to assess that neither India nor China wants a war and that both will maintain a more constant contact with each other as they search for ways to find a solution from which they can both emerge as winners. The core of the guidance provided by the leadership is that the two countries regard each other as a partner, not adversary.

Now, this unstable equilibrium reached at Chushul-Moldo border meeting point will not last if the Malabar exercises turn into a geopolitical tool for Washington to transform QUAD. China had hitherto blithely assumed that QUAD is a mere. papa tiger.

Evidently, the US is stuck in the old Cold War groove despite the drastic changes in international relations that have taken place since the collapse of the Soviet Union, especially those that required the development of new approaches to maintaining strategic stability and building a new architecture of international security.

But the US’ bloc thinking is the opposite of the development of stable, equal, constructive, mutually beneficial relations based on consideration of each other’s interests and aimed at ensuring equal and indivisible security for all. Therefore, its preservation as the main intellectual tool for shaping foreign policy only underscores that the US is not ready, unable or does not intend to build such relations with leading global players such as Russia and China. Implicit in it is a stark message for India, too, that the time has come for it to stand up and be counted as ally.

There is no doubt that the US envisages a pronounced military-strategic dimension to AUKUS and QUAD, which means a high probability of transformation of these interstate associations as cogs in the wheel of a full-fledged military-political bloc sooner rather than later. Its ideological basis is a perceived common interest of its participants to counter the rise of China [which nowadays Delhi euphemistically calls ‘‘multipolar Asia’’].

Suffice to say, as in the case with the NATO on the European theatre, the function of confrontation is planted in the AUKUS and in QUAD, which will inexorably increase the military potential of Australia and the US in the Asia-Pacific region, causing a serious change in the balance of forces and generating a spike in regional and global tensions.

India is at risk of being caught in the eye of the storm, as it were, although its issues with China are neither one of geopolitical rivalry nor of being a gatekeeper for Western hegemony.

Read more here.

The Quad maritime offensive

By Tom Corben (amended)

Australia's hosting of Exercise Malabar provides opening for deeper cooperation. Although not officially a Quad activity, Malabar has effectively functioned as one since Australia rejoined the drills in 2020, following Japan's accession as a permanent partner five years before.

After the disappointment of the last-minute cancellation of May's planned Quad leaders' summit in Sydney amid the U.S. debt limit standoff, hosting Malabar will be ample consolation for Australia.

From an initial focus on building familiarity between participants' navies, these exercises have evolved to focus on increasingly sophisticated forms of high-end naval cooperation, particularly maritime domain awareness and anti-submarine warfare.

It will also present an opportunity for Canberra to advocate taking Quad naval cooperation to a higher level to give the grouping "more muscle" so it can live up to its potential as a regional maritime defense collective.

Fortunately, there is a political and strategic window of opportunity for the four countries to make good on this potential.

Successive leaders' summits and the growing sophistication of the Malabar drills show how the Quad has coalesced around a common strategic logic, with the pursuit of shared maritime security interests and the balancing of China's regional influence as central elements.

Yet conversation about a Quad maritime security agenda is only possible because of the increasingly sophisticated defense cooperation that has been taking place between two or three Quad members at a time.

This shows that an effective Quad maritime security agenda need not look like all four partners doing everything, everywhere, all at once. Instead, the members can take advantage of naval cooperation already taking place below the Quad level through coordinating operations, standardizing information-sharing procedures and opening more military facilities to one another for maintenance and sustainment purposes.

More effectively aligning these activities would help to amplify measures that the four countries are already taking, both independently and with partners, to respond to Chinese military activities across the Indo-Pacific region.

New developments in the U.S.-Australia alliance could have a big role to play in operationalizing this agenda.

Successive joint meetings of Australian and U.S. defense and foreign affairs ministers, in the institutionalized format known as AUSMIN, have demonstrated how the alliance's force posture initiatives, joint exercises and combined military operations are as much about supporting a wider collective defense agenda as they are about supporting the U.S. military presence in Asia alone.

For instance, the joint statement issued after last month's AUSMIN flagged the creation of a maritime domain awareness initiative that will see more frequent rotations of U.S. Navy maritime patrol aircraft through Australian facilities.

The critical inclusion of a reference to "inviting likeminded partners to participate" at a later date suggests that countries like India or Japan, which has already been invited to integrate into U.S.-Australia force posture initiatives, could send aircraft to participate in joint maritime surveillance activities launched from Australian air bases in the near future.

This is exactly the kind of initiative required to advance a strategy of collective defense in Asia. Yet it is also not entirely groundbreaking, as these activities would fit into a broader tapestry of cooperation that the Quad partners are already undertaking in twos and threes across the region.

India's leadership here deserves special attention, for its activism defies conventional skepticism that New Delhi's preference for nonalignment and its geostrategic priorities militate against deeper military cooperation with its Quad partners.

Evidence from the Indian Ocean tells a different story, showing India leading collective maritime surveillance activities with its Quad partners. Consider a few recent developments.

At the height of India-China border tensions in October 2020, a U.S. maritime patrol aircraft refueled at Port Blair on India's Andaman and Nicobar Islands at a facility traditionally shielded from foreign access and insight. Japan is helping India to further develop those facilities, and its Maritime Self-Defense Force is paying increasingly frequent visits.

As part of a new enhanced maritime surveillance initiative, Indian and Australian maritime patrol aircraft have also conducted at least four extended visits to one another's naval air facilities for joint exercises and coordinated patrols within the last 18 months. Last month, over 30,000 troops from 13 nations descended on Australia to take part in the country's biennial Talisman Sabre military exercises with the U.S.

These activities are great examples of how Quad countries can leverage their strategic geography, military infrastructure and common capabilities to implement a strategy of collective deterrence where and when their political and strategic priorities align.

Formalizing U.S.-Australia maritime surveillance cooperation would fit with that agenda, too. Conducting joint or coordinated activities with Quad partners out of Australian facilities would do much to improve the collective picture of Chinese naval activity in littoral Southeast Asia and the eastern Indian Ocean.

To be sure, possibilities for a Quad maritime security agenda are not boundless. Lingering bureaucratic, political and resource constraints across the four member countries will dictate how fast and how far they can move together.

But clearly, progress is being made. The outcomes from this year's AUSMIN demonstrate that bilateral efforts are continuing to open the aperture for tangible Quad maritime defense cooperation.

Rather than through the Quad itself, it is these sorts of developments that will give quiet but valuable expression to Quad naval cooperation beyond the confines of Malabar.

Read more here.