Theatre of War

Can US Indo-Pacific military manoeuvring make headway against a sinking AUKUS alliance and ASEAN's non-proliferation and non-interference principles?

UPDATE: Regional states seek to avoid another US-led war, or any war in Asia. However, the news cycle is exploding with US military repositioning as opposition to its regional offensives build strength. Today, the Long Mekong Daily provides a front line report on the “theatre of War” in East and Southeast Asia. Japan is in dire economic straits, but like the US is printing money to finance military expansion. The US ASEAN policy has hit a dead end with Indonesia while the AUKUS nuclear submarine alliance is sinking in the face of ASEAN’s policy of non-proliferation. Australia appears to be quietly navigating the AUKUS arrangement into the deep water of financial, and technical difficulties. India’s participation seems limited to the near waters and high valleys of the Quadrilateral Dialogue. The Philippines military is marching to the Duterte drumbeat and Cambodia suffers from US interference in its domestic politics. Forward March!

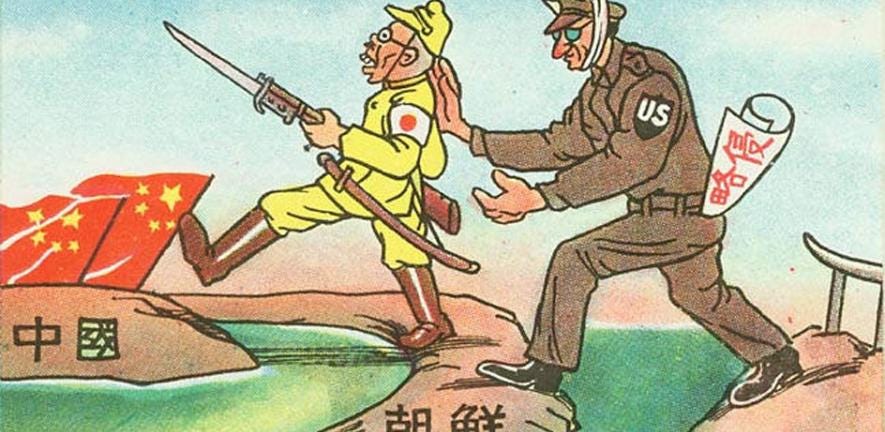

US military “setting the theatre” for war with China

In a remarkably frank interview with the Financial Times yesterday, the top US Marine general in Japan declared that US-NATO successes against Russia in Ukraine were a product of advance planning and preparations—“setting the theatre” for war in military jargon. That was exactly what the Pentagon was doing in Japan and Asia, he explained, in preparing for conflict against China over Taiwan.

“Why have we achieved the level of success we’ve achieved in Ukraine?” Lieutenant General James Bierman asked rhetorically. A big part of it, he explained, was that after what he termed “Russian aggression” in 2014 and 2015, “we earnestly got after preparing for future conflict: training for the Ukrainians, pre-positioning of supplies, identification of sites from which we could operate support, sustain operations.”

“We call that setting the theatre. And we are setting the theatre in Japan, in the Philippines, in other locations.” In other words, the US is setting a trap for China by goading it into taking military action against Taiwan in the same way that it provoked Russia into invading Ukraine following the US-backed coup in 2014 that toppled a pro-Russian government.

Lieutenant General James Bierman is commanding general of the Third Marine Expeditionary Force (III MEF) and of Marine Forces Japan. Significantly, the III MEF is the only Marine crisis response force permanently stationed outside the US. In other words, Bierman and his Marines would be on the front line of any US-led conflict with China.

As the Financial Times explained, the III MEF is “at the heart of a sweeping reform of the Marine Corps.” Its focus is being shifted from the “war on terror” in the Middle East to “creating small units that specialise in operating quickly and clandestinely in the islands and straits of east Asia and the western Pacific to counter Beijing’s ‘anti-access area denial’ strategy.”

The US plans for war against China—known as AirSea Battle—envisage a massive air and missile assault on Chinese military bases and strategic industries supported by warships and submarines. The Pentagon has been increasingly concerned about China’s military abilities to defend its territory and secure neighbouring seas—“anti access area denial” with its own missiles and naval vessels.

US war preparations with Japan are proceeding apace. As Bierman boasted, the two militaries have “seen exponential increases . . . just over the last year” in their activities on territory from which they would operate during a war. In recent exercises, the Marines for the first time established bilateral ground tactical co-ordination centres rather than liaising with a separate Japanese command point.

The aim is far closer integration of American and Japanese forces. Instead of Japanese military groups being rotated to operate alongside US forces in Japan, specific units have now been designated as part of the “stand-in force” alongside their US Marine, Navy and Air Force counterparts.

Bierman also pointed out that similar preparations are being made in the Philippines where the government intends to allow the US to preposition weapons and other supplies on five more bases in addition to five where it already has access. “You gain a leverage point, a base of operations, which allows you to have a tremendous head start in different operational plans,” he enthused.

The US-led war against Russia in Ukraine and its intensifying confrontation with China are two sides of a strategy to dominate the vast Eurasian landmass that threatens to plunge humanity into a nuclear holocaust.

While Bierman is highlighting the advanced operational planning for war with China, it is being matched by huge increases in military spending by both the US and Japan.

Read full article here.

Japan Approves 26.3% Increase in Defense Spending for Fiscal Year 2023

Even as it faces severe headwinds for its economy and the Yen’s rapid fall from grace, for the ninth year in a row, the budget draft set a new record for Japan’s national defense budget. China, North Korea, and Russia are acting as if to wake a long-time sleeping lion in Asia – that is, Japan.

On December 23, the cabinet of Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio approved 6.82 trillion yen ($51.4 billion) in defense spending in fiscal year 2023, starting in April, amid what it calls “the most severe and complex security environment since World War II.”

Including U.S. Forces realignment-related expenses allocated for mitigating impacts on local communities, the draft budget will rise by a whopping 26.3 percent, or 1.42 trillion yen, from the current fiscal year. This marks yet another record figure, continuing a streak of nine consecutive years of increases of Japan’s national defense budget under a Liberal Democratic Party (LDP)-led administration.

The draft budget, which is expected to be passed by Japan’s bicameral legislature in the coming months, comes in at around 1.19 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), up from 0.96 percent in the current fiscal year. Tokyo plans to increase defense spending to the NATO standard of 2 percent of GDP in 2027.

The draft budget listed seven priority areas to “drastically strengthen Japan’s defense capabilities.” Those are (1) “stand-off defense capabilities,” such as mass production of longer-range missiles; (2) “Integrated Air and Missile Defense (IAMD) capabilities” to defend against adversarial missile attacks; (3) “unmanned asset defense capabilities” such as the use of drones; (4) “cross-domain operational capabilities” in the space, cyberspace, and electromagnetic domains; (5) “command and control and intelligence-related functions”; (6) “maneuvering and deployment capability” to send troops and supplies to the front line; and (7) “sustainability and resiliency” of the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF).

Read more here.

Biden’s Half-Hearted Policy Towards Southeast Asia

Washington has stepped up its game in the region but is constrained by its unwillingness to do trade deals. Even though Southeast Asia is a strategic region in the emerging U.S.-China standoff, the Biden administration’s policy toward it in 2021 left much to be desired. During its first year in office, the Biden team lacked a strategy for the region, was short on ambassadors, and paid little attention to cultivating top-level ties. But in 2022, the administration stepped up its game in the region by showing up in person, clarifying its approach in key strategy documents, and boosting cooperation through initiatives such as the elevated Comprehensive Strategic Partnership between the United States and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). But heavy lifting remains: The administration still has no viable economic strategy, its emphasis on containing China threatens to alienate key countries in the region, and prioritizing a values-based foreign policy is a non-starter in a region of mostly authoritarian and semi-authoritarian states.

One crucial improvement in 2022 was that the administration made a point of actually showing up. Especially after two years of only virtual engagement due to the pandemic, high-level, face-to-face meetings are a prerequisite for success on issues and policies. Last November, U.S. President Joe Biden personally attended three critical multilaterals: the U.S.-ASEAN and East Asia summits in Cambodia, as well as the G-20 summit in Indonesia. Although Biden did not participate in the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in Thailand—he was at his granddaughter’s wedding at the White House instead—he sent Vice President Kamala Harris to attend in his stead. Other high-level visits included U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s trips to Cambodia, Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines; Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin’s travels to Cambodia, Indonesia, and Singapore; and Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman’s visit to Laos, the Philippines, and Vietnam.

But showing up in Southeast Asia was not the only way the administration stepped up its engagement. In May, Biden hosted a historic U.S.-ASEAN Special Summit at the White House, bringing together nearly all ASEAN leaders. (Myanmar’s junta leader was not invited, and then-Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte did not attend due to his country’s impending presidential election.) Although the outcome was thin on actual policy deliverables, the summit was a signal that the United States still wields significant influence, despite China’s growing political, economic, and military clout in the region.

Read full article here.

Indonesia-Australia: Deeper divide lies beneath AUKUS submarine rift

Indonesia, the new ASEAN chair for 2023, is committed to “standing in the middle” between the United States and China and using ASEAN as a buffer. Jakarta has serious concerns about the impact Australia’s acquisition of nuclear-power submarines might have on regional security and non-proliferation.

AUKUS is just the tip of a deep and enduring divide between Australia and Indonesia over the future of power in the Indo-Pacific.

Indonesia’s initial response to the creation of AUKUS was critical, and it was subsequently announced in mid-October that Jakarta would seek a review of the Non-Proliferation Treaty in a bid to prevent states without nuclear weapons from acquiring nuclear-powered submarines. This was followed by at first indirect and then direct criticisms of AUKUS issued by senior Indonesian ministers alongside China’s then Foreign Minster Wang Yi.

Australia’s state run media (ABC) reported that Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo had “repeatedly and forcefully” raised concerns about AUKUS with then Prime Minister Scott Morrison when they met virtually with leaders of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

Despite this recent diplomatic divide over AUKUS, Australia has become more steadfast in its preference for US leadership. However, the new Albanese government seems to be quietly unravelling the former governments anti-China belligerence, excessive defense spending and dependence on the US and incompetent management of existing and expensive military procurement programs.

Although the United States and Australia have starkly different views on some aspects of foreign policy – most notably trade and geo-economic policy – Canberra explicitly supports Washington’s efforts to maintain its global leadership role. With the AUKUS security partnership and the AUSMIN announcement of more US forces to be hosted in Australia, Canberra is deepening its military embrace of Washington and as a consequence positioning itself to assist with the execution of US grand strategy.

For security observers, AUKUS is seen as a catalyst to unleashing nuclear armament acquisition arguments in Indonesia, Japan and possibly South Korea. ASEAN is firmly against proliferation, correctly viewing the AUKUS arrangement as a stepping stone in the US attempt to constrain and even prepare for a theatre of war in the Western pacific.

AUKUS Nuclear Submarine Deal Sinks

In two seperate letters the Australia, United Kingdom (AUKUS) trilateral military alliance has begun to unravel. The new Labor government in Australia and the new Australian Ambassador to Washington, former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, appear to be undermining the costly and dangerous AUKUS deal opposed by France, China and Indonesia.

The story so far: A group of United States politicians has written to President Joe Biden to strongly defend the AUKUS pact and insist American shipyards are up to the task of providing Australia with a stopgap supply of nuclear-powered submarines before the retirement of Australia’s problem prone Collins-class fleet.

The nine members of the House of Representatives – both Democrat and Republican – were responding to a letter to Biden last month from two senior US senators warning the AUKUS pact risked pushing America’s industrial base to “breaking point”.

The two powerful US politicians Senator Jack Reed and Senator James Inhofe, have raised serious concerns about the AUKUS pact, warning President Joe Biden the proposal to help Australia acquire nuclear-powered submarines risked harming America's industrial base to "breaking point". In a leaked letter dated December 21, first obtained by US publication Breaking Defense, the Democratic Chair of the Senate Armed Services Committee and a former Republican colleague outline their anxieties over the ambitious project.

"Over the past year, we have grown more concerned about the state of the US submarine industrial base as well as its ability to support the desired AUKUS SSN [nuclear sub] end state."

Committee chair, Senator Jack Reed, and Republican Senator James Inhofe warn the White House explicitly against any plan to sell or transfer Virginia-class submarines to Australia before the US Navy meets its current requirements.

"We believe current conditions require a sober assessment of the facts to avoid stressing the US submarine industrial base to the breaking point," the Senators are quoted as saying.

"We are concerned that what was initially touted as a 'do no harm' opportunity to support Australia and the United Kingdom and build long-term competitive advantages for the US and its pacific allies, may be turning into a zero-sum game for scarce, highly advanced US SSNs."

Their dramatic intervention comes just three months before the Albanese government unveils its nuclear submarine plan and is the first time members of Congress have raised major concerns about AUKUS, which enjoys bi-partisan support in Washington.

In August a senior US Navy official also warned helping Australia acquire nuclear-powered submarines could be too big a burden for America's already overstretched shipyards.

Read full story here.

India remains divided about AUKUS

The possibility of Australian submarines in the Indian Ocean isn’t reassuring for India’s security observers. The jury in New Delhi is still out on AUKUS, the trilateral security agreement between the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia. Three months after its announcement, the issue continues to split India’s security experts, with little consensus over whether it benefits New Delhi or is detrimental to Indian interests.

Many believe the pact is useful for India and its Indo Pacific partners. By clearly declaring its intention to deter China, AUKUS, proponents say, expands New Delhi’s options in dealing with Beijing. Moreover, the pact opens up a window of opportunity for more strategic collaboration between India and France.

As some others see it, the continuing turbulence on India’s northern border makes it imperative for New Delhi not to be part of an anti-China alliance. Supporters say AUKUS allows India – a key US partner and a vital Indian Ocean player – the leeway to engage with China at terms acceptable to New Delhi. In a post-pandemic world, Indian policymakers must also prioritise challenges in the non-military domain – vaccine diplomacy, infrastructure building, technology sharing and climate change – without feeling the need to sign up to a China-containment coalition. The agreement allows New Delhi to focus on its developmental agenda, with a degree of assurance that the strategic threat in the Indo-Pacific would be robustly met.

But sceptics disagree. However noble its intended purpose, AUKUS, they aver, subverts the strategic order in Asia. First, it is baldly provocative to China, which could potentially destabilise the Western Pacific (with inevitable consequences for Indian Ocean states). Second, the pact’s intended aim – to build Australia’s naval muscle – does not mitigate India’s strategic challenge in the Himalayas. More importantly, AUKUS is prejudicial to French interests. By alienating Paris, it injects distrust in the Western alliance. That, too, could have unintended consequences.

From a maritime operations perspective, AUKUS gives Indian observers pause. With the Indian navy’s conventional underwater capability fast shrinking, the possibility of Australian submarines in the Indian Ocean isn’t reassuring for India’s security observers. While they are happy for Australia – a Quad member and close partner of India in the Indo-Pacific – to receive nuclear submarine technology from the United States and the United Kingdom, Indian watchers apprehend a crowd of friendly nuclear attack subs in the Eastern Indian Ocean. Increased foreign submarine presence in India’s near-seas would serve only to erode Indian influence and authority in the neighborhood.

New Delhi is also troubled by the prospect of an AUKUS-generated backlash from China. The agreement could provoke Beijing into expanding military activity in the littorals – not so much in the congested South China Sea, already gridlocked with posturing and counter posturing, but in the Indian Ocean, where China has so far been relatively quiet. The Chinese navy could assume a more adventurous posture in the Eastern Indian Ocean, deploying more warships and submarines. China’s ships may well stay clear of Indian waters, but their mere presence in the littorals is bound to put more pressure on India’s naval leadership. In response, New Delhi might have to deploy Indian warships in the South China Sea, pushing India-China maritime dynamics into a negative spiral.

Read more here.

Lt. Gen. Andres Centino Regains Philippine Military Chief Post After Only 5 Months

The government did not provide any explanation for the replacement of Lt. Gen. Bartolome Bacarro, who was supposed to serve until August 2025. Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. on Saturday cut short the term of the military chief of staff he appointed five months ago and replaced him with a retiring general without explaining the surprise move.

Marcos’s office announced the replacement of Lt. Gen. Bartolome Bacarro, who had received the highest military award for combat bravery. A statement late Friday did not specify any reason for the change in military leadership. Bacarro’s three-year term was supposed to end in August 2025.

The appointment of military chiefs is a sensitive issue. The military has a history of restiveness, failed coup attempts, and corruption scandals and has faced accusations of human rights violations. Efforts have been made for years to instill professionalism in the military and insulate it from the country’s traditionally chaotic and corruption-tainted politics.

Lt. Gen. Andres Centino, the military chief of staff who Bacarro replaced in August last year, was installed by Marcos to the top post of the 144,000-strong armed forces. Centino, who was due to retire next month, was chosen over a dozen senior generals and will have a fresh three-year term.

Read full story here.

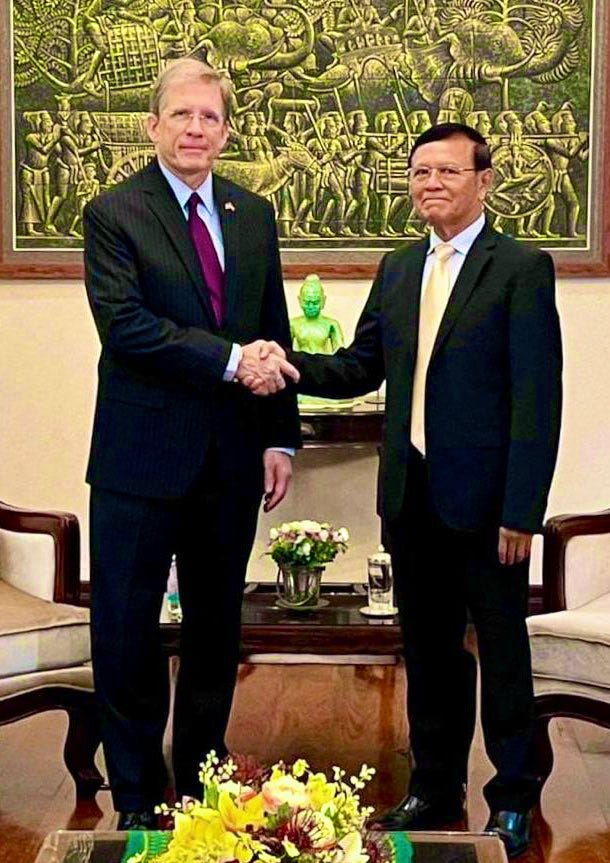

The US Seeks to Influence Treason Trial and Cambodian Elections

US Ambassador to Cambodia Patrick Murphy visited liberal right-wing Cambodian politician Kem Sokha to voice U.S. support for inclusive, multi-party democracy in Cambodia. Kem Sokha was arrested for treason on September 3, 2017, accused by the government of conspiring with the United States to overthrow the Royal Government of Cambodia (RGC). He has denied the charges and says his only goal was to take power democratically. The case is in its final stages and a verdict is expected on 3 March 2023.

His political career began in 1993, when he was elected a representative for Takéo Province as a member of the Buddhist Liberal Democratic Party. The BLDP was run by the wealthy landowner and anti-communist Son Sann. In the wake of the 1970 coup against Prince Norodom Sihanouk, Son Sann was arrested and fled to France. During the late 1980s and early 1990s, Son Sann received military and financial support from the United States. Following Cambodia's Paris Peace Agreement, Son Sann formed a new political party, the Buddhist Liberal Democratic Party in 1992 and participated in the 1993 elections. President of the National Assembly from June to October 1993, Son Sann left Cambodia for Paris in 1997 and died in 2000.

Following the demise of Son Sann’s political movement, Ken Sokha joined the royalist FUNCINPEC in 1999 and was subsequently elected a senator. He resigned from his Senate seat in 2001. In 2002, Kem Sokha announced he was leaving politics and founded a human rights group called the Cambodian Center for Human Rights (CCHR). He left the center to establish a new political party called Human Rights Party (HRP) in 2007.

Connection to Sam Rainsy

In 2012, the HRP merged with the Sam Rainsy Party (SRP) to form the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP). Kem Sokha is known for his phrase "Do Min Do" (Change or no change), which attempted to mobilise Cambodian youth in the 2013 election campaign. Kem briefly served as a First Vice President in the national assembly in 2014-15. In 2016, Kem was sentenced to five months in prison after refusing to appear in court for questioning in a prostitution case against him. He was later granted a royal pardon by King Norodom Sihamoni.

Kem Sokha became the vice president of the CNRP and became its president in March 2017 after the discredited Sam Rainsy resigned. Rainsy fled Cambodia for Paris to avoid life imprisonment on charges of “attempting to hand over a part of national territory to a foreign entity.” Prime Minister Hun Sen has said that Rainsy's family [father and grandfather] have been traitors to Cambodia.

Sam Rainsy and the Bangkok Plot

Sam Rainsy's father, Sam Sary, had served as a minister and deputy prime minister in Norodom Sihanouk's government in the 1950's. Sam Rainsy is married to Tioulong Samura, who’s father, Nhiek Tioulong, was a military general and founder of the Khmer Renovation party, who briefly served as Prime Minister in 1962. Sam Sary fled Cambodia in 1959 after the failed Bangkok Plot or Dap Chhuon Plot. The conspiracy was an attempt to topple Prince Norodom Sihanouk of Cambodia, and was initiated by Sam Sary and other right-wing politicians, including Son Ngoc Thanh, and governor Dap Chhuon a regional Cambodian warlord. The conspiracy was supported by the US dominated Thailand and South Vietnam governments and US intelligence services. The Bangkok Plot and its politics still influence Cambodian politics today as US backed politicians continue their attempts to undermine and displace the independence parties that have governed the country since 1953.