Warlords

Hemedti, RSF, Darfurian Arabs & Janjaweed. Latin America's outlaws, drug cartels & crime syndicates. Zelensky's warlord oligarch. China's Warlords ruled from 1916 until 1949.

UPDATE: Hemedti’s RSF is led by Darfurian Arabs known as Janjaweed. The term refers to the armed groups of Arabs from Darfur and Kordofan in western Sudan. Drawn from the far west of the country’s periphery, they have – in a mere decade – become the dominant power in Khartoum. And Hemedti has become the face of Sudan’s violent, political marketplace.

In Latin America, tens of millions of people live in territories that are governed by outlaws — from powerful drug cartels to crime syndicates. At the beginning of 2023, the state of Sinaloa endured hours of violence as Mexican authorities hunted down and captured Ovidio Guzmán, the son of the famous drug trafficker Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán.

A notorious “warlord oligarch” accused of keeping sharks in his office to intimidate foes has had his home raided in Ukraine. The SBU, Ukraine’s security service has not commented on the raid but unnamed officials quoted in Ukrainian media said it was part of an investigation into claims Mr Kolomoisky embezzled about £1 billion from two oil companies where he was once a majority shareholder.

Warlords “did more harm for China in sixteen years than all the foreign gunboats could have done in a hundred years.” Warlords struggled for power between the death of would-be Emperor Yuan Shikai in 1916 and the Nationalists, led by Jiang Jieshi, retreated to Taiwan in 1949. Nationalist holdouts dominated remote frontier provinces until 1950; some of their lieutenants fought a decade later to control drug trafficking in the Golden Triangle.

Warlord Sudan

Edited

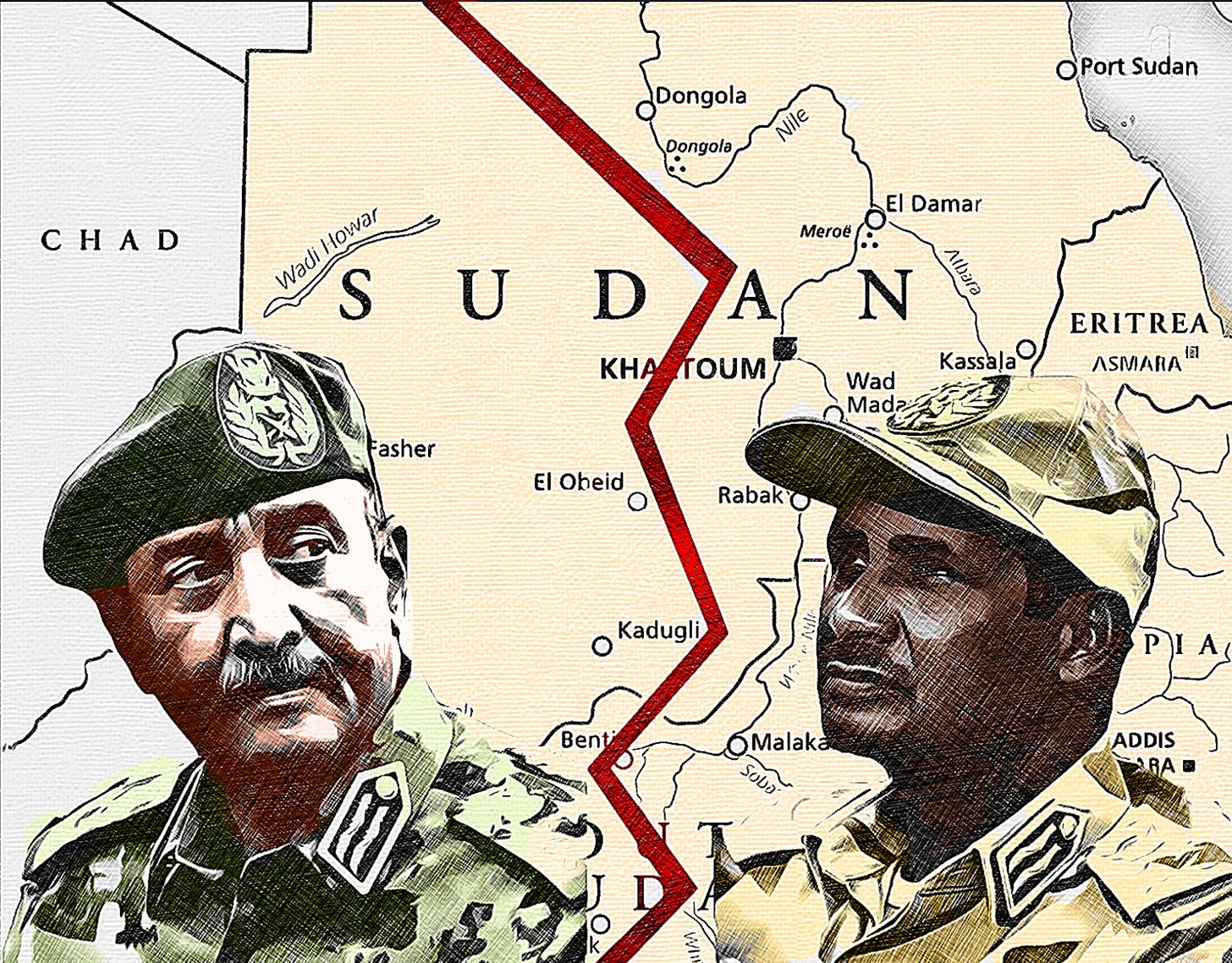

Dozens have been killed in armed clashes in the Sudanese capital Khartoum following months of tension between the military and the powerful paramilitary group Rapid Support Forces (RSF). Behind the tensions is a disagreement over the integration of the paramilitary group into the armed forces – a key condition of a transition agreement that’s never been signed but has been adhered to by both sides since 2021.

General Mohamed Hamdan Dagolo, better known as Hemedti, is the leader of the RSF. He is a key mover in the fast-escalating civil war, as he has been in other key moments in Sudan’s recent history. Hemedti’s RSF is led by Darfurian Arabs known as Janjaweed. The term refers to the armed groups of Arabs from Darfur and Kordofan in western Sudan. Drawn from the far west of the country’s periphery, they have – in a mere decade – become the dominant power in Khartoum. And Hemedti has become the face of Sudan’s violent, political marketplace.

Hemedti’s career is an object lesson in political entrepreneurship by a specialist in violence. His conduct and (as of now) impunity are the surest indicator that politics of the mercenary kind that have long defined the Sudanese periphery, have been brought home to the capital city.

Hemedti is from Sudan’s furthest peripheries, an outsider to the Khartoum political establishment. His grandfather, Dagolo, was leader of a subclan that roamed across the pastures of Chad and Darfur. Young men from these camel-herding, landless and marginalised group became a core element of the Arab militia that led Khartoum’s counterinsurgency in Darfur from 2003.

A school dropout turned trader, Hemedti has no formal education. The title ‘General’ was awarded on account of his proficiency as a commander in the Janjaweed brigade in Southern Darfur at the height of the 2003-05 war. A few years later, he joined a mutiny against the government, negotiated an alliance with the Darfurian rebels, and threatened to storm the the government-held city of Nyala.

Soon Hemedti cut a deal with the government. Khartoum would settle his troops’ unpaid salaries and compensation for the wounded and killed. He got promotion to general and a handsome cash payment. After returning to the Khartoum payroll, Hemedti proved his loyalty. President Omar al-Bashir who ruled Sudan from 1993 to April 2019 when he was deposed became fond of him, sometimes appearing to treat him like the son he had never had.

But, in the days after Bashir was overthrown, some of the young democracy protesters camped in the streets around the Ministry of Defence embraced him as the army’s new look. Back in the fold, Hemedti ably used his commercial acumen and military prowess to build his militia into a force more powerful than the waning Sudanese state.

Al-Bashir constituted the RSF as a separate unit in 2013, initially to fight the rebels of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army-North in the Nuba Mountains. The new force came off second best. But, with a fleet of new pickup trucks with heavy machine guns, it soon became a force to be reckoned with, fighting a key battle against Darfurian rebels in April 2015.

Following the March 2015 Saudi-Emirati military intervention in Yemen, Sudan cut a deal with Riyadh to deploy Sudanese troops in Yemen. One of the commanders of the operation was General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan who has chaired the Transitional Military Council since 2019. But most of the fighters were Hemedti’s RSF. This brought hard cash direct into Hemedti’s pocket.

And in November 2017, Hemedti’s forces took control of the artisanal gold mines in Jebel Amer in Darfur — Sudan’s single largest source of export revenues. This followed the defeat and capture of his arch-rival Musa Hilal, who rebelled against Al-Bashir.

Suddenly, Hemedti had his hands on the country’s two most lucrative sources of hard currency. Hemedti is adopting a model of state mercenarism familiar to those who follow the politics of the Sahara. The late President Idriss Déby of Chad rented out his special forces for counter-insurgencies on the French or US payroll in much the same manner.

On the other hand, with the routine deployment of paramilitaries to do the actual fighting in Sudan’s wars at home and abroad, the Sudanese army has become akin to a vanity project. It is the proud owner of extravagant real estate in Khartoum, with impressive tanks, artillery and aircraft. But it has few battle-hardened infantry units. Other forces have stepped into this security arena, including the operational units of the National Intelligence and Security Services, and paramilitaries such as special police units — and the RSF.

Every ruler in Sudan, with one notable exception, has hailed from the the heartlands of Khartoum and the neighboring towns on the Nile. The exception is the Khalifa Abdullahi “al-Ta’aishi” who was a Darfurian Arab. His armies provided the majority of the force that conquered Khartoum in 1885. The riverian elites remember the Khalifa’s rule (1885-98) as a tyranny. They are terrified it may return.

Hemedti is the face of that nightmare, the first non-establishment ruler in Sudan for 120 years. Despite the grievances against Hemedti’s paramilitaries, he is still recognised as a Darfurian and an outsider to the Sudanese establishment.

When the Sudanese regime sowed the wind of the Janjaweed in Darfur in 2003, they least expected to reap the whirlwind in their own capital city. In fact the seeds had been sown much earlier. Previous governments adopted the war strategy in southern Sudan and southern Kordofan of setting local people against one another. This was preferred to sending units of the regular army -— manned by the sons of the riverain establishment — into peril.

Hemedti is that whirlwind. But his ascendancy is also, indirectly, the revenge of the historically marginalised. The tragedy of the Sudanese marginalised is that the man who is posing as their champion is the ruthless leader of a band of vagabonds, who has been supremely skillful in playing the transnational military marketplace.

Read more here.

Warlord Latino

Excerpts

In Latin America, tens of millions of people live in territories that are governed by outlaws — from powerful drug cartels to crime syndicates. At the beginning of 2023, the state of Sinaloa endured hours of violence as Mexican authorities hunted down and captured Ovidio Guzmán, the son of the famous drug trafficker Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán. Blockades, shootings and citizens locked in their homes: It was a stark demonstration that in Latin America, there are places where the state does not govern but, instead, the criminals — in this case the Sinaloa Cartel — are in charge.

Mexico is an iconic case, but not the only one. In Ecuador, for example, the state has lost control in its overcrowded prisons, where criminal organizations extort money from detainees and their families, and also carry out massacres inside prison walls. Seven such massacres in 2021 and 2022 claimed the lives of more than 350 people.

In the absence of armed conflict, Latin America has the highest rates of violence in the world. According to 2018 data from the Economic Commission for Latin America, the region has 10 times more homicides (23 per 100,000 inhabitants) than Europe (2.1 per 100,000) and about eight times more than Asia (2.7 per 100,000). Of these homicides, 93 percent are concentrated in Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, Venezuela, El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, countries that are home to only 68 percent of Latin America’s population.

Part of this violence is the product of criminal governance, the process by which criminals — paramilitary groups, vigilantes, death squads, guerillas, drug cartels, organized crime groups and gangs — take over the traditional role of the state and govern or co-govern a territory and a population. There are areas in Latin America where criminals have taken charge of maintaining public services, building infrastructure and even dispensing justice.

“Most societies in this region are grappling with patterns of criminal governance through which state officials, political authorities and organized crime actors co-govern. While the phenomenon is certainly not new, it has attained greater prominence as ever more influential and powerful criminal syndicates have entered into the bloodstream of many societies, transforming traditional forms of governance,” ( Annual Review of Sociology).

The difference has to do with the notion of governance. Organized crime is motivated by profit; its objective is not to govern. Criminal governance is a context in which criminal groups govern spaces, population and territory. The Sinaloa Cartel in Mexico governs several communities where the population knows that the state does not have the capacity to intervene. In Rio de Janeiro, the Amigos dos Amigos gang rules Rocinha, one of the main favelas of this Brazilian city.

There are studies in Brazil on how these criminal groups administer justice in sectors where there is no justice, where there is total impunity with respect to robberies, sexual assaults and other incidents in the communities. These organized crime groups have a parallel justice system where they manage these types of problems, and the communities value this very much, as in the case of Rocinha, in Rio. Inhabitants of this favela say they feel safe, and criminal groups have been shown to settle property rights issues between neighbors and provide public services, recreation and sports.

In Brazil, a mixture of structural conditions (poverty, inequality, marginalisation and hopelessness) generates violence, and the state, through its coercive arm (police, army, security forces) acts violently, often committing abuses that are not investigated, let alone punished, in an atmosphere of impunity. A plurality of actors use violence to achieve their ends. Different manifestations of violence overlap: criminal, political and economic.

It is a tremendously complex phenomenon. A significant portion of the population lives marginalized from society, with low schooling, high poverty and high unemployment, and one of their few existing options is to join a criminal structure. Materialism and nihilism are recurring themes for the youth who enter this type of structure. They long for a life of glamour and a life of consumption and are willing to pay the ultimate sacrifice. Many of them tell you: I would rather spend five years as a sicario (hit man), but live them well, than spend 50 years in a demeaning job, being exploited, and overwhelmed by so much scarcity.

Finally, I would say that there is a strong state issue: states that are not capable of providing alternatives, or whose models are not attractive. The formal model of studying, of trying to get ahead, is very uncertain: It requires a lot of sacrifice and is not necessarily seen as attractive. Contexts of criminal governance in countries like Uruguay and Costa Rica are very prevalent and go under the radar because people focus on the most emblematic cases, like Mexico, Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela, Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras. But this is a much deeper problem and has to do with the weakening of state structures and the loss of the state’s legitimacy. These two elements undermine state capacity.

If you look at the levels of violence, this is a very strong indicator of how the coercive apparatus of the state in countries like Costa Rica and Uruguay has been weakening in the last 10 or 15 years. Homicide rates, although lower than in other nations in the region, have doubled in those two countries.

In country after country, states have withdrawn from many areas because they don’t have the capacity — and sometimes the will — to govern those areas. That vacuum has been filled by criminal actors. The only hope is that societies and political actors understand the seriousness of the issue and form governments of national unity in which politically antagonistic sectors put aside extremist attitudes, make concessions and seek common solutions to the problems of governance. It is essential to forge a sustainable development model that provides the state with the conditions to raise the population’s standard of living. The challenge is monumental.

Read more here.

Zelensky’s Warlord Oligarch

A notorious “warlord oligarch” accused of keeping sharks in his office to intimidate foes has had his home raided in Ukraine. The SBU, Ukraine’s security service has not commented on the raid but unnamed officials quoted in Ukrainian media said it was part of an investigation into claims Mr Kolomoisky embezzled about £1 billion from two oil companies where he was once a majority shareholder.

Ihor Kolomoisky was once regarded as one of Ukraine’s most powerful men, with majority shares in oil companies, a major bank and the TV channel that launched Volodymyr Zelensky’s comedy career before he entered politics.

Mr Kolomoisky is credited with helping Mr Zelensky win the 2019 presidential election, throwing the weight of his media empire behind him during the campaign. The Ukrainian president denies being supported by the tycoon.

He once attempted to forcibly take over a steel plant by deploying “hundreds of hired rowdies” armed with chainsaws and baseball bats, according to Forbes. And according to another report, he previously filled the reception of a rival Russian oil company with coffins.

Despite multiple corruption scandals and his verbal attacks on journalists, Mr Kolomoisky did not face any pressure from government until recently, mainly because he was often hailed for fighting ethnic Russian separatists in eastern Ukraine in 2014. Shortly after he was appointed governor of Dnipro in the spring of 2014, Mr Kolomoisky diverted part of his fortune to hire and train volunteers to fight the separatists in the Donbas.

The oligarch’s fortunes began to sour in 2021 when the US sanctioned him because of “significant corruption” during his time in office as Dnipro governor. The sanctions were seen as an effort from Washington to steer Mr Zelensky away from the influence of powerful oligarchs. Mr Zelensky clamped down on oligarchs a couple of months before the Russian invasion when in November 2021, he introduced a bill banning them from owning majority states in strategic sectors of the economy.

Last summer, Mr Zelensky reportedly stripped Mr Kolomoisky of Ukrainian citizenship, paving the way for him to be extradited to the US where he is being investigated for money laundering. The raid at Mr Kolomoisky’s home appears to be part of a major anti-corruption sweep as Ukrainian investigators on Wednesday also unveiled corruption charges against Kyiv’s top customs official, while a former senior official at the defence ministry will face charges of embezzlement.

Read more here.

Warlord China

Usually translated into English as “warlords,” junfa were the bane of Republican China. Some were highly trained officers, others selfmade strategists or graduates of the “school of forestry,” a Chinese euphemism for banditry. In the words of a contemporary, they “did more harm for China in sixteen years than all the foreign gunboats could have done in a hundred years.” Warlords struggled for power between the death of would-be Emperor Yuan Shikai in 1916 and the Nationalists retreat to Taiwan in 1949. Holdouts dominated remote frontier provinces until 1950; some of their lieutenants fought a decade later to control drug trafficking in the Golden Triangle.

Warlords began their rise to power during the 1911 Revolution that ended millennia of imperial rule. Leaders like dentist-turned-revolutionary Sun Yat-sen argued Western-style Republicanism was the new standard for governance. To succeed, a republic needed support from China’s armed forces and their commander, Yuan Shikai. A rocky marriage between this wily general and Sun ended with the former elected as China’s first president. Yuan never connected to Republicanism and shortly before his death attempted an imperial restoration (1915–16). His demise unleashed the warlords, who quickly carved China into a hodgepodge of nearly independent states.

Chinese, who suffered from their misrule, were all too familiar with the warlords. Sun Yat-sen, acclaimed “Father of the Republic,” denounced them as “a single den of badgers.” Progressives regarded these militarists as a malignant force whose collective actions factionalized the nation. Junfa, the Chinese word for warlord, soon became a loaded pejorative for misuse of authority.

Zhang Zongchang was born to a practicing witch, and his father was an alcoholic musician. As an adult, he was a self-described graduate of “the school of forestry” and at six-foot-six was the tallest of the warlords. His troops terrified local civilians—famous for their rapacity and “splitting melons” (bashing skulls with rifle butts). Zhang was the epitome of the wicked warlord. His life was so notorious that it is difficult to separate history from slander. All that was bad in 1920s China was laid at his door; victims and enemies magnified Zhang into a poster boy for evil and avarice.

Feng Yuxiang was different. While the bemedaled Zhang proudly sported an opulent marshal’s uniform, Feng was more likely to appear in the quilted gray tunic of a private soldier. Another tall warlord, he was a convert to Methodism, thus nicknamed the “Christian General.” Feng was also noted for his highly disciplined troops that paid for any requisitions and rarely abused civilians. Next, he morphed into the “Red General” after turning to the USSR for military support. The “Lying General” was another pejorative, bestowed by enemies who succumbed to Feng’s crafty tactics. Indeed, Huang Huilan, a well-connected contemporary, described him as the “Tricky Warlord”; it was said he could even double-cross himself. Issues of treachery aside, Feng’s place in Chinese popular culture is very different from Zhang’s. The Christian General is not seen as a warlord but rather a patriot, steadfast in his opposition to imperialism and an early proponent of total war with Japan. He is also remembered for attacks on foot binding, reforestation of the northwest, and an austere personal life that is probably the most stark contrast to the flamboyant Zhang.

Yet travel back to Tianjin on December 29, 1925, as Feng’s soldiers yanked Xu Shuzheng out of his train, then shot him in the back of the head. “Little Xu” had been a warlord and was still connected to Feng’s enemies. He had also killed Feng’s relative, Lu Jianzheng, under very similar circumstances in 1918. Always economical, the Christian General’s murder of Xu gained both revenge and eliminated a rival.

The willingness to use violence for political gain marked the warlord. Feng had very different agendas from Zhang, but both men spilled copious quantities of blood to gain their objectives. This might be on the battlefield or on a very personal level, like the murder of Little Xu.

A few warlords came from prosperous families, but most were from peasant stock. Zhang was a Shandong man, born in 1881; Feng was born nearby in Zhili (Hebei) Province a year later. Both grew to manhood under the Qing dynasty and were saddled with less-than-stellar parents. As both men rose through the ranks, with the help of patrons, they became connected to warlord alliances, often called cliques. Feng joined the Zhili Clique, whose star was Wu Peifu, the “Jade Marshal.” A master tactician, Wu was that rare warlord with a classical education. Zhang followed a more circuitous route to the Fengtian Clique, whose chairman was the unrelated Zhang Zuolin, the so-called “Tiger of Manchuria.” These alignments guaranteed Feng and Zhang would become enemies, for both cliques sought to dominate Beijing, the weak but still valuable capital of China.

The realities of 1920s Chinese warfare were intense. By the mid-1920s, warlord armies could include more than 500,000 soldiers. With armored trains or old-fashioned rifles and swords, warlord soldiers fought bloody contests from 1916 to 1928. Successful generals learned not only to deploy an infantry brigade or conduct aerial operations, but also how to employ treachery. For instance, generals might use “silver bullets” (bags of silver dollars) to encourage key enemy players to switch sides. Offers of cash, power, or revenge reached high levels in the 1920s, leading Wu Peifu to complain that “betraying one’s leader has become as natural as eating breakfast.” Zhang could play this game, but when it came to treachery, Feng was an authority.

Feng’s greatest triumph was the 1924 betrayal of Wu Peifu, an event that completely unhinged the formidable defenses at Lengkouguan Pass. This ended Wu’s career but propelled Feng to the top ranks of the warlords. Ironically, the betrayal also helped Zhang, who conquered this part of the Great Wall, gaining significant credit within the Fengtian Clique.

By 1925, Feng became hostile to the “unequal treaties” that privileged European, American, and Japanese interests. Via posters, plays, songs, and instruction, his soldiers were told they served the Guominjun, or National Army, and were indoctrinated on the evils of imperialism. This stressed that their service was not simply to a warlord, but rather in support of the nation. Simultaneously, Feng accepted military aid from the USSR, allowing reporters to coin yet another nickname, the “Red General.”

Keeping track of Zhang’s nicknames required a score card. He was the “Dog Meat General,” a northern Chinese euphemism that recorded his extreme fascination with a domino-like game called pai jiu. Huang Huilan recalled him arriving at poker games with sacks full of silver dollars. He may have paid his soldiers in worthless script, but gambling debts were sacred and required hard money. Zhang was also the “Three Don’t Knows General,” supposedly because he could never say how many soldiers were under his command, how much money he owned, or the number of his many wives and concubines.

The careers of Zhang and Feng meshed in the mid-1920s. The former, with his White Russian mercenaries in front, raced down to capture Shanghai after Wu’s debacle. Feng, now aligned with the Fengtian Clique, continued plotting. On November 5, 1924, his troops expelled Puyi from the Forbidden City, declaring the former emperor a simple citizen of the Republic. This sent Puyi into the arms of militarists like Zhang, who gathered significant wealth in exchange for vague promises of support. In the end, Feng’s actions drove this Manchu royal to Japan, laying groundwork for the puppet state of Manchukuo and Puyi’s infamous role as China’s number one Quisling.

Read more here.